Regional elections in Saxony and Thuringia – a reflection of a social and political crisis in Germany

Thuringia and Saxony have elected – there will be no “business as usual”, and not just in eastern Germany.

René Zittlau

The forecasts were largely accurate. In Saxony, things went badly for the parties in power in Berlin, narrowly missing the worst-case scenario. In Thuringia, good advice is not only in short supply for the old parties. The Sarah Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) must now also show its true colors.

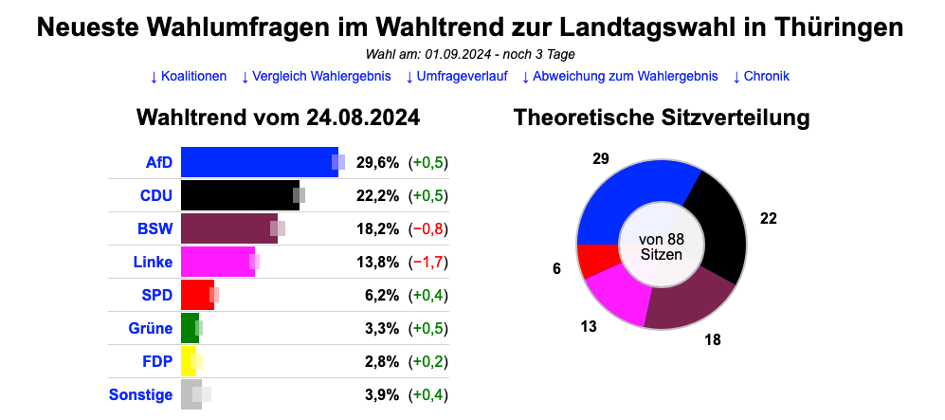

The regional elections in Saxony and Thuringia thus largely confirm the pre-election forecasts that we published in the article “Germany, your zero hour?” a few days ago.

Even if the worst predictions for the Berlin coalition did not quite come true, the provisional official final results pose enormous problems for the parties in Saxony, Thuringia and above all in Berlin.

Saxony – the “red socks” save the CDU

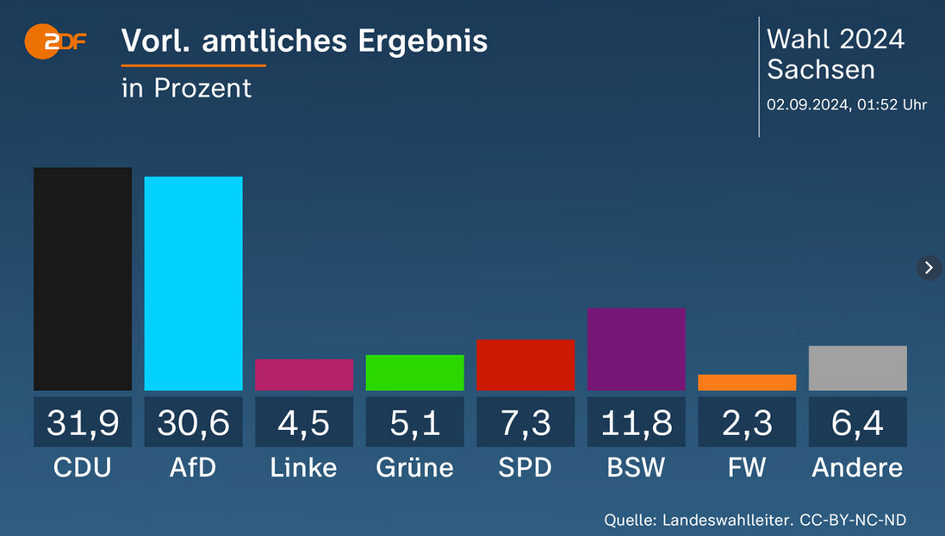

These are the provisional final results of the regional elections in Saxony:

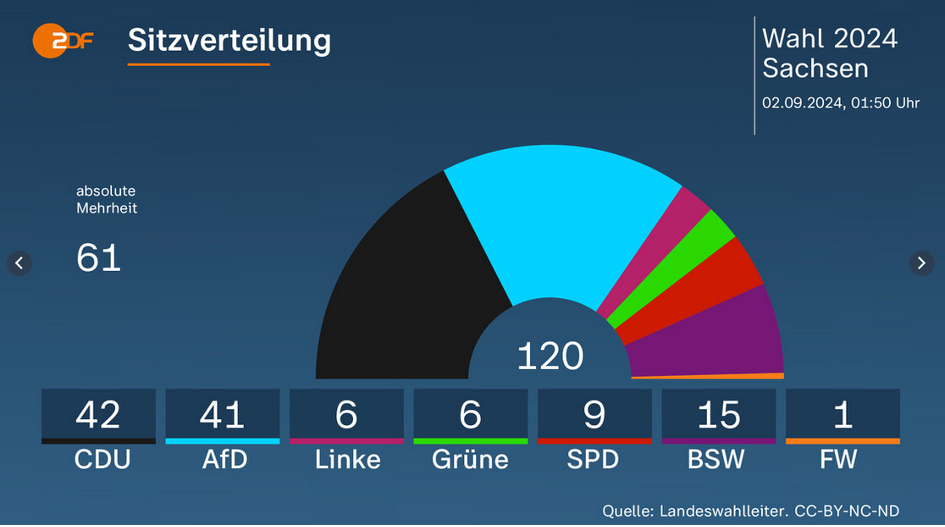

The fact that the LINKE won two direct mandates is the only reason why it entered the state parliament with the strength of the second votes it received, even though it did not achieve 5% of the votes. Based on the resulting distribution of seats, these two direct mandates are likely to tip the scales and save the CDU from having to kowtow to the BSW.

In order to form a majority, 61 seats are needed in the Saxon state parliament. Without the left-wing seats, the CDU would have to reach an agreement with the BSW in order to form a government. The CDU has categorically ruled out working with the AfD.

For the CDU, the entry into the Saxon state parliament of DIE LINKE, which it once fought against as “red socks”, is an absolute stroke of luck both in Saxony and, above all, in Berlin.

Without the LINKE, the Saxon CDU would have to rely on any kind of alliance with the BSW in order to form a government. However, in the run-up to the election, the BSW had made it a condition of government participation that the CDU turn away from its bellicose policies not only at state but also at federal level.

This coincidence of the will of the electorate means that the absolute worst-case scenario for the CDU has probably been averted once again by the LINKE, of all parties, which just a few years ago was fought just as fiercely by the CDU using questionable constitutional methods with the help of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, as is happening today with the AfD. The opponent changes, the methods remain the same for the CDU.

Nevertheless, the political realities in Saxony are unlikely to suit either the CDU Saxony or the Berlin traffic light parties. Thus, after some high-profile back and forth, the only possible coalition in Saxony is likely to be a government of CDU, SPD, Greens and LINKE – a toxic political mix that only became conceivable thanks to the political devastation of the Merkel years. An impossibility under “normal” conditions.

Thuringia – the German political system is reaching its limits

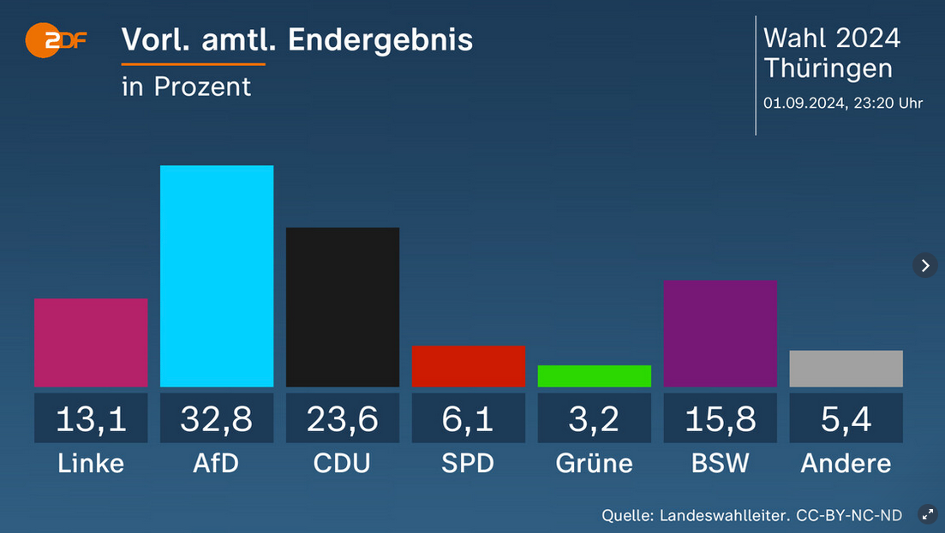

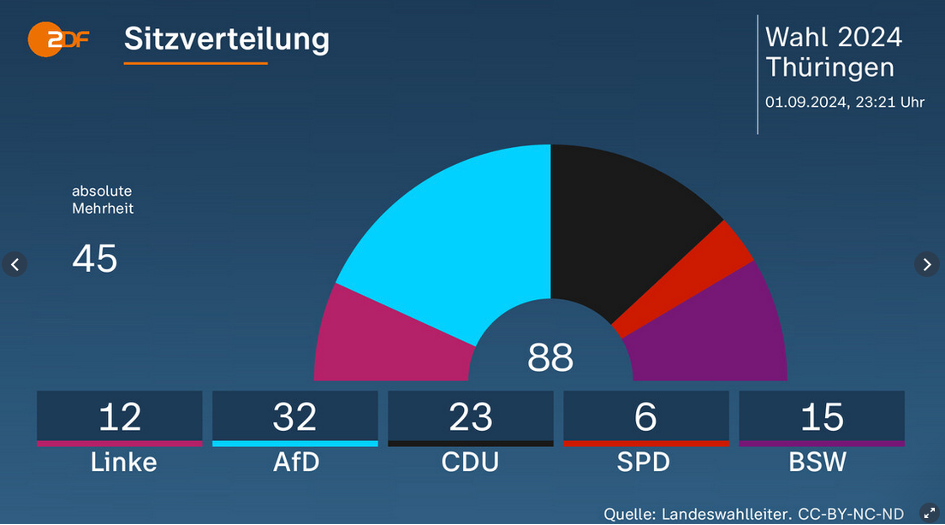

In Thuringia, too, we first look at the provisional official final result:

The AfD has emerged victorious from the elections by a large margin.

The distribution of seats resulting from the provisional official final result will bring us turbulent coalition negotiations in the coming weeks and possibly months.

They will be highly problematic because, despite all assurances, the distribution of seats does not suit anyone’s concept.

Normally, the winner of the election is tasked with forming a government, i.e. the AfD. However, in the run-up to the election and in the knowledge of the result, all parties ruled out any form of cooperation with the AfD. Nevertheless, the AfD could well be tasked with forming a government, simply to show its political powerlessness.

At the same time, the BSW asserted – as we said above – that it would only enter into coalition negotiations with the CDU if the latter abandoned its war policy, not only at state level but also in Berlin.

The absolute majority in the Thuringian state parliament is 45 seats. The conditions for possible coalitions repeatedly and vehemently put on record by the various parties make any majority government impossible under these conditions.

Even a minority government of the CDU tolerating the BSW would provoke considerable questions to the BSW, even if the condition were fulfilled that the BSW would not participate in a CDU government if the CDU did not renounce its course of war.

In addition, there is no tradition of minority governments in Germany. The only such case was the so-called “Magdeburg model”, an SPD minority government tolerated by the PDS from 1994 to 2002, which was under constant pressure from all sides, including the federal SPD. Chancellor Kohl, for example, called the PDS, which tolerated the SPD, “red-painted fascists”.

The crisis of the political system in Germany is part of the political crisis of the European Union

The seemingly broad political spectrum reflected in the results of the two regional elections could in itself be evidence of a very high-profile, differentiated political landscape. With respect and tolerance towards political opponents, new, unusual political alliances should also be possible in order to fulfill the will of the voters, without anyone sensing any kind of threat to political order and stability.

Whereas 20-30 years ago there was still a certain respect for political opponents, which ultimately led to tolerance of views that did not correspond to one’s own interpretation of politics, in the last 10-15 years a political relentlessness has taken hold across Europe that mercilessly combats any dissent with all available means. In the process, elements of the rule of law are often used that are difficult to reconcile with justice and the law in the traditional sense. We discussed this in the article “Germany, your zero hour?” using the example of Federal Interior Minister Faeser and the head of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, Haldenwang.

The consequence of this tendency, which can be observed in practically all European Union states, is that political developments and election results are only accepted and recognized by the ruling parties and movements if they serve the continuation of their own agenda. Any deviation to the left or right is fought against with all severity and at all levels as “extremist”, “extreme right”, “extreme left” and therefore outside the norm.

Solving the tasks at hand requires the discussion of all ideas that can contribute to the solution

The mainstream refers almost daily to the fact that the AfD is at least suspected of being right-wing extremist, if not directly right-wing extremist.

On May 13, 2024, the Tagesschau declared:

“The Office for the Protection of the Constitution was right to classify the AfD as a suspected right-wing extremist party. The Münster Higher Administrative Court confirmed the ruling of the lower court – and thus rejected the party’s appeal.”

So it’s official in court: the AfD is right-wing extremist. Or is it not?

Because it’s not that simple. When researching the definition of the term “right-wing extremism”, no clear criteria can be found.

The Federal Agency for Civic Education, after all, as a higher federal authority in the division of the Federal Ministry of the Interior, reports to the same minister as the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, which monitors the AfD, which has been judicially classified as “certainly right-wing extremist”, writes, for example:

“Because right-wing extremism itself does not have a homogenous ideological concept, there is no standard definition for the term.”

You can read further there:

“In the practice of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, the following characteristics are seen as indications of right-wing extremist aspirations. These are listed in the literature as characteristic of a right-wing extremist world view:

- an aggressive nationalism that is only guided by German interests and regards other nations as “inferior”,

- the desire for a national community on a ”racial” basis, which arbitrarily restricts the rights of the individual and opposes the pluralistic society with the model of ”popular collectivism” (”You are nothing, your people are everything”),

- anti-pluralism

- aggressive, extremely violent xenophobia as a result of a revival of racist and associated anti-Semitic ideas

- the desire for a ”leader state” with military principles of order (militarism)

- relativization or even denial of the crimes of the “Third Reich” and the associated trivialization or glorification of National Socialism and

- a constant defamation of democratic institutions and their representatives.”

Furthermore, right-wing extremist views are incompatible with the free democratic basic order, which is defined by the Federal Agency for Civic Education as follows:

“Fundamental principles of the free democratic basic order are (following the ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court of 1952):

- Respect for the human rights set out in the German Basic Law, especially the right of the individual to life and free development

- Sovereignty of the people

- Separation of powers

- Government accountability

- Legality of the administration

- Independence of courts

- Multiparty principle

- Equal opportunities for all political parties with the right to form and exercise an opposition in accordance with the constitution.”

So if the AfD is judicially deemed to be “assuredly right-wing extremist”, it should be possible to find corresponding manifestations in the AfD’s policy documents. And if this is the case, then it should be possible to ban such a party in court and ban it from political life.

The AfD’s basic program comprises 95 pages. There are plenty of theses that can hardly be reconciled with the current government policy in Berlin. Contradiction is the task of the political opposition and should be an indispensable part of a functioning marketplace of political ideas, as long as these political ideas do not contradict the legal framework of the state – in the case of Germany, the Basic Law.

No transgression of this framework is discernible in the program.

The once “red socks” seem to have secured a government majority for the CDU in Saxony. It would be time, in the interests of the country and out of respect for the voters, to bring all forces on board that have ideas for tackling the country’s huge problems.

Conclusion

Regardless of the outcome, one thing is clear: an ever-increasing proportion of Western populations no longer support the decisions of their governments. Not only in Germany, but also in France, other European countries and the US. The majority of Western governments are making decisions over the heads of their populations – guided by incompetence and megalomania originating in Brussels and Washington.

2 thoughts on “Regional elections in Saxony and Thuringia – a reflection of a social and political crisis in Germany”