The American Economy According to Emmanuel Todd

Donald Trump is reshaping the global economic order by reviving protectionism. He defends higher tariffs as essential to curbing the fentanyl influx, revitalizing industry and reducing the trade deficit. His economic policies are as polarizing as they are thought-provoking. Emmanuel Todd offers valuable insights into the underlying dynamics of the American economy.

Auguste Maxime

In a recent interview with Le Figaro, Emmanuel Todd stated: “What is happening definitively and solidly is Russia’s victory in the East. We are experiencing a defeat. The Western bloc is being defeated, and we are in the process of disintegration.” An iconoclastic figure in the French intellectual landscape, Todd is at once an anthropologist, sociologist, and demographer.

He became well-known for predicting the collapse of the Soviet Union fifteen years before it occurred. Without knowing Russian or ever setting foot in the USSR, he demonstrated in The Final Fall (1976), using demographic and educational indicators, that the Soviet Union was in structural decline. By analyzing official data and international reports, he highlighted a rise in infant mortality and a slowdown in scientific and technological progress. Initially dismissed as provocative, his conclusions ultimately proved accurate.

His approach follows the tradition of the Annales School, a movement founded in France by Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre in the 1920s. This school profoundly reshaped historiography by adopting a global and interdisciplinary perspective, combining quantitative methods and deep structural analysis of societies. Instead of focusing on events or historical figures, it emphasizes long-term dynamics—economic, social, and cultural—that shape civilizations over time.

The U.S. Trade Deficit: An Imperial Levy

At the dawn of the 2000s, at the peak of what some called “American hyperpower,” Emmanuel Todd already discerned, in the U.S. military intervention in Iraq, the early signs of its decline. In After the Empire (2003), he argued that something unprecedented was happening in the relationship between the United States and the rest of the world.

He observed that the United States had a structurally growing trade deficit with all its major partners: China, Japan, Europe, Mexico, and South Korea. In other words, the U.S. imported far more goods than it exported, particularly manufactured products.

Its trade deficit increased from approximately $100 billion annually in 1993 to over $450 billion by 2000. By 2024, it had soared to nearly $1.2 trillion.

According to Emmanuel Todd, this phenomenon is atypical in the history of empires. In a classical empire, the center dominates the periphery through its production and industry, exploiting the resources of its colonies—labor, raw materials, and taxes. In contrast, the U.S. no longer derives its power from production but from consumption.

As the US trade deficit widens, so do the foreign capital flows needed to finance it. Indeed, every country’s balance of payments must be balanced. Nations such as China and Japan finance the U.S. by recycling their trade surpluses into U.S. Treasury bonds. Their economic model depends on exports and requires an undervalued currency to maintain competitiveness. Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, their central banks have been free to create local currency ex nihilo—whether yuan or yen—to purchase U.S. dollars. These dollars are then reinvested in U.S. Treasury securities, a highly liquid and secure asset. This mechanism simultaneously keeps their currency weak and funds the U.S. external deficit.

Thus, these countries produce more than they consume, allowing Americans to consume more than they produce. Consequently, the U.S. trade deficit is not just an economic imbalance, but rather, according to Todd, a genuine imperial levy—a system through which the U.S. captures a disproportionate share of global wealth to sustain its way of life. American military interventionism, therefore, serves as a deterrent against any challenge to this imperial privilege.

However, this model comes at a cost: by allowing increasingly advanced imported manufactured goods to replace domestic production, the U.S. sacrifices its industrial base in favor of foreign competitors, accelerating its transformation into a service-dominated economy.

In The Defeat of the West (2020), Emmanuel Todd observes that the United States’ dependence on the rest of the world has reached a critical threshold. With the Ukrainian conflict, Americans are realizing that they are unable to supply enough weapons to Kyiv to win the war. Yet, on the eve of the conflict, the combined GDPs of Russia and Belarus represented only 3.3% of the total GDP of the United States and its allies—Canada, Europe, Japan, and South Korea.

Todd also highlights that cutting-edge technologies crucial to the artificial intelligence race, such as semiconductors, are now largely concentrated on the periphery of the empire: in Taiwan, South Korea, or Japan. The deindustrialization of the United States now directly threatens its hegemony, hence Donald Trump’s desire to introduce tariff barriers to attempt to counteract it.

Healthcare System: “Paying More to Die Sooner”

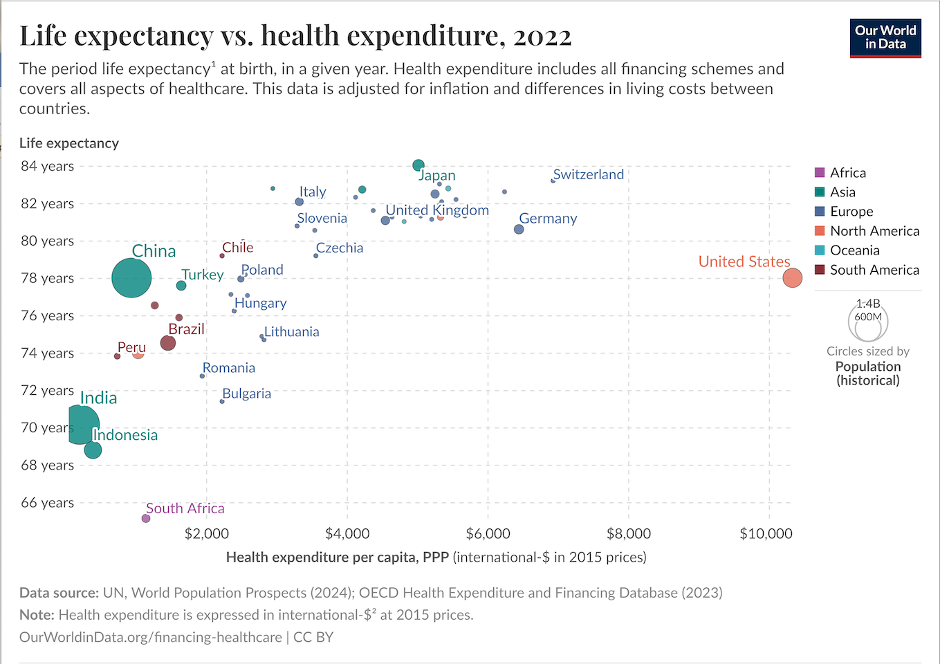

Life expectancy in the United States is following a concerning trajectory. After decades of progress, it stagnated in 2010 before beginning a significant decline in 2014. The U.S. is the only major power to experience such a regression. In 2014, life expectancy reached 78.8 years before plummeting to 77.3 years in 2020 and further dropping to 76.3 years in 2021. This decline widens the gap with other developed nations: 80.7 years in the United Kingdom, 80.9 in Germany, 82.3 in France, 83.2 in Sweden, and 84.5 in Japan.

More than a simple demographic indicator, life expectancy reflects a country’s economic and social health, more specifically the efficiency of its healthcare system, level of education, social organization and inequalities. According to Emmanuel Todd, this deterioration is the sign of a profound dysfunction in American society.

Among the key drivers of this decline, cardiovascular diseases linked to obesity and diabetes and the opioid crisis are frequently cited. While the former results from chronic conditions exacerbated by an unhealthy lifestyle, the latter represents a true epidemic of addiction and excess mortality, fueled by the widespread prescription of opioids and the proliferation of synthetic drugs. In 2021, overdoses caused over 100,000 deaths in a single year, with 70% linked to opioids.

This crisis has its roots in the 1990s when pharmaceutical companies promoted these substances as revolutionary painkillers, deliberately downplaying the risks of addiction. Doctors prescribed these medications in large quantities to treat chronic non-cancer pain (back pain, osteoarthritis, etc.). Many patients, having become dependent, transitioned to illicit opioids, particularly heroin and fentanyl—a synthetic opioid up to 50 times more potent than heroin.

The opioid scandal exposes the systemic failures of the American healthcare system and the outsized influence of pharmaceutical firms, whose economic interests—often in collusion with certain doctors—have led to catastrophic health and social consequences. As Todd notes: “We are indeed witnessing the actions of certain elite groups whose decisions devastate part of the population.”

Infant mortality rates—an essential barometer of a society’s future—are equally alarming. A country that fails to effectively protect its newborns reveals a deep crisis, regardless of its apparent economic power. Unlike economic indicators such as unemployment, inflation, or GDP, which can be easily manipulated by a government, the infant mortality rate remains a raw and indisputable measure.

According to Todd, a country where infant mortality worsens is entering a phase of structural and political decline. According to UNICEF, in 2020, this rate was 5.4 per 1,000 live births in the U.S., compared to 4.4 in Russia, 3.6 in the U.K., 3.5 in France, 3.1 in Germany, 2.5 in Italy, 2.1 in Sweden, and just 1.8 in Japan. For Todd, infant mortality is also strongly correlated with a country’s level of corruption: nations with the lowest rates tend to be the least corrupt, like Scandinavia and Japan.

Paradoxically, the decline in public health has been accompanied by an explosion in healthcare spending. The United States has the highest healthcare costs in the world. In 2020, these expenses accounted for 18.8% of U.S. GDP, compared to 12.2% in France, 12.8% in Germany, 11.3% in Sweden, and 11.9% in the U.K. These percentages are even more alarming when considering Americans’ theoretical level of wealth. In 2020, GDP per capita was $76,000 in the U.S., compared to $48,000 in Germany, $46,000 in the U.K., and $41,000 in France.

In other words, Americans spend more than any other nation on healthcare… yet their life expectancy and overall well-being are declining. This contradiction raises questions about the relevance of GDP as a true measure of a country’s prosperity.

What Is the True Value of U.S. GDP?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was developed during the Great Depression by Russian-American economist Simon Kuznets as a way to quantify economic activity. It measures the total value of goods and services produced within a country over a specific period. GDP became a crucial tool during World War II, when governments needed to align economic planning with the demands of the war effort.

After the war, under the influence of international institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, GDP became the benchmark indicator for measuring economic growth, solidifying its central role in international economic policy.

In The Defeat of the West (2020), Emmanuel Todd questions the relevance of GDP in measuring the real wealth of the American economy. He argues that in an economy where nearly 80% of activity comes from the service sector, this indicator—designed when the U.S. was still a heavily industrialized nation—overestimates the value created by services.

To evaluate the real wealth generated each year by Americans, Todd distinguishes between “tangible production” and services. The former includes sectors that produce concrete goods essential to the functioning of the economy, such as industry, agriculture, construction, and transportation. He considers these activities to be the source of real, measurable, and indispensable wealth, as they rely on transforming raw materials and building fundamental infrastructure.

By contrast, he categorizes services separately, including finance, law, administration, segments of the medical sector, higher education, and various business and consumer services. According to Todd, these sectors are harder to evaluate in terms of genuine value creation, with some being overvalued or even parasitic.

What is the actual economic contribution of a doctor who prescribes harmful treatments? What wealth is created by an economist whose forecasts are consistently wrong? What tangible value does an overpaid lawyer, a predatory financier, a prison guard, or an intelligence agent bring to the economy?

To assess GDP per capita, Todd draws on John Maynard Keynes’ famous principle: “It is better to be approximately right than precisely wrong.” He examines the healthcare sector, which accounts for 18.8% of U.S. GDP—nearly double the levels seen in Europe, even as American life expectancy declines. He estimates that only 40% of this spending corresponds to real value and applies this reasoning broadly to the service sector.

Thus, if services represent 80% of U.S. GDP, or $60,800 per capita, Todd argues that their actual value is overestimated by 60%, adjusting it to $24,320. He then adds the contribution from productive sectors, such as agriculture and industry, which he keeps unchanged at $15,200 per capita, as they represent tangible wealth. By summing these two values, he estimates the “Real Domestic Product” per capita at $39,520—a figure significantly lower than the official GDP per capita of $76,000.

Conclusion

According to Emmanuel Todd, the strength and prosperity of the American economy are built on a statistical illusion. While official indicators like GDP, inflation, and unemployment suggest stability, they mask deeper structural weaknesses. The U.S. is living beyond its means, rapidly deindustrializing, and, in the process, weakening its military and geopolitical leverage.

Perhaps the most telling signs of decline are not found in economic data but in public health: life expectancy is falling, and infant mortality is rising. These aren’t just statistical outliers—they’re symptoms of a broader societal crisis. GDP, when examined critically, paints an overly optimistic picture, inflating the wealth generated by a service-heavy economy while downplaying the country’s growing dependence on debt and foreign capital.

Faced with these realities, the recent shift toward protectionism looks less like a simple political maneuver and more like an attempt to stem the tide of industrial decline. Tariff barriers, once dismissed as outdated policy, are now being rebranded as economic self-defense. There’s a growing recognition that decades of unregulated globalization may have hollowed out the nation’s productive base. But the real question remains: can these policies do anything more than slow the bleeding?

For Todd, this crisis is not just another economic downturn—it’s a structural rupture, one that could permanently alter America’s position in the world. If he’s right, then the U.S. is not just struggling to maintain its economic dominance; it may be approaching the end of it.

17 thoughts on “The American Economy According to Emmanuel Todd”