Auguste Maxime: The US is Approaching a “Debt Death Spiral”

Legendary investor Ray Dalio warns that the United States could “go bankrupt” within the next three years, triggering political and geopolitical consequences. In his latest book, How Countries Go Broke, he describes the mechanics of the American “Big Debt Cycle”.

Auguste Maxime

Dalio recently compared the US debt to “plaque” obstructing the financial system, gradually constraining the government’s ability to function. As interest payments consume an ever-larger share of revenues, the risk of a financial “heart attack” looms.

U.S. national debt now exceeds $36 trillion, or around 125% of GDP, to which the government adds nearly $1 trillion every 100 days. Annual interest payments have surpassed $1 trillion a year, even outpacing defense spending. The country continues to record budget deficits of around 7% of GDP, despite a growing economy and unemployment below 4%. If such deficit persists during “good times”, how catastrophic might they become during a recession?

With 50 years’ experience as a macro investor, Dalio has developed a unique framework for understanding the economy and debt markets. Founder of Bridgewater Associates, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, he has become a much-followed figure since the 2008 financial crisis. He believes the US government is now in the late stages of its “Big Debt Cycle”, a phase in where financial imbalances become unsustainable.

What’s the Big Debt Cycle?

Every time someone makes a transaction using credit, a cycle begins. A purchase financed by credit allows a person to spend more today than his available budget, but forces him to spend less tomorrow to repay the debt. If the borrower is unable to repay his debt, he goes bankrupt and the lender takes his loss.

While this dynamic is well understood for individuals and corporations, few people understand that the logic remains the same for sovereign states. Perhaps that’s because governments can take on much more debt, and for much longer, than most people could imagined. Some argue that a state can never go bankrupt because it can always “print money”. But as Ray Dalio argues, nothing could be further from the truth.

Governments, like individuals and companies, can go broke because they are subject to the same financial constraints. They have balance sheets that record their assets (what they own) and liabilities (what they owe), as well as income statements that track their revenues and expenditures. If liabilities outweigh assets and expenses exceed revenues, including debt servicing, they face three options: reduce spending, restructure its obligations, or default.

But unlike individuals or companies, governments have two powerful tools at their disposal: fiscal power through taxation and spending, and monetary power through money creation and credit expansion. These levers enable governments to manage debt crises, but not without pain. The challenge is to identify the warning signs of debt restructuring and understand who will ultimately bear the cost.

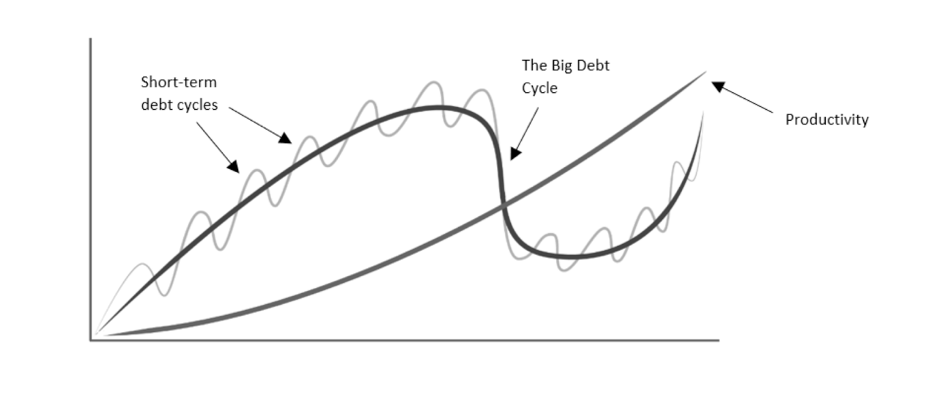

To this end, Dalio breaks down the economy into three major forces: productivity, short-term cycles and the long-term debt cycle.

Productivity is the main driver of long-term economic growth. It increases over time, thanks to human ingenuity and technological progress. Productivity is what enables living standards to rise over the long term.

Short-term debt cycles are also known as “business cycles”. They result from fluctuations in economic activity driven by changes in the availability of credit. Lasting around 6 years on average, these cycles begin when economic growth and inflation are low. The central bank reduces interest rates to encourage borrowing by households and businesses. As one person’s spending is another’s income, this borrowing fuels economic growth. When the economy overheats and inflation begins to rise, the central bank raises interest rates. This has the effect of tightening credit conditions, slowing economic activity and, eventually brings inflation under control. If the economy falls into recession, the central bank reduces the cost of money again, starting a new cycle.

The long-term debt cycle, also known as the “Big Debt Cycle” generally lasts around 75 years. Over the course of multiple short-term cycles, debt steadily accumulates until it reaches unsustainable levels. Eventually, the system becomes saturated: debt grow disproportionately large relative to income. The central bank is faced with an impossible trade-off: creditors demand higher rates to continue lending, while debtors can no longer afford to do so. Faced with this dilemma, governments almost always choose to sacrifice the creditors. In practice, this means printing money to buy debt, which devalues both the currency and debt itself. The big difference between the short-term debt cycles and the “Big Debt Cycle” is that the latter cannot be reversed by stimulating the economy with massive injections of liquidity. According to Dalio, the US economy is approaching the peak of its “Big Debt Cycle”, which began in 1944, and the phase of deleveraging is about to begin.

How did we get there?

In How Coutries Go Broke, Dalio describes the evolution of the “Big Debt Cycle” in various ways. One is the development of the monetary regimes piloted by the US government to accompany it since 1944. He also outlines the two that are likely to follow.

Bretton Woods Agreement or the Hard Money System (1944–1971)

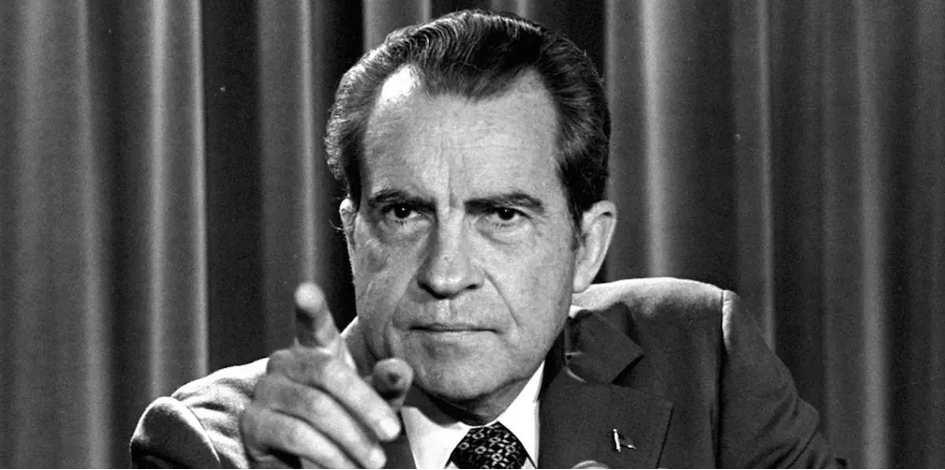

Following the 1944 agreement, Western currencies were pegged to the US dollar, which in turn was backed by gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. This constraint imposed strict discipline on the supply of money and credit. The dollar was considered a worthless currency, but exchangeable for gold, the real money. This monetary system limited public spending by providing a rigid framework for borrowing. But from the 1960s onwards, the United States accumulated large budget and trade deficits as a result of the Vietnam War and the “Great Society” programs. Countries accumulating trade surpluses with the US, such as France, realizing that the Americans were issuing more dollars than they had gold reserves, began to reclaim their precious metals, triggering a “bank run” dynamic. The system collapsed in 1971 when President Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold, ushering in the era of fiat currency.

Source: Boston Globe

Fiat Money & Interest Rate Management (1971–2008)

With the end of the gold standard, the quantity of money and credit was no longer constrained, but determined by interest rates, controlled in part by the central bank. By raising or lowering interest rates, central banks could encourage borrowing and spending or cool down inflation. This new system granted governments a great deal of power. Now, they could influence the value of money to ease the burden of debt and confiscate wealth through inflation. This system has enabled significant economic growth, but it has also favored debt accumulation and trade and financial imbalances. Asset bubbles and financial crises became more frequent. The economy increasingly relied on credit and low interest rates to grow. This phase culminated in the global financial crisis of 2008. The public sector was forced to take on massive debt to cover the over-indebtedness and bankruptcy of the private sector. Interest rates were reduced to zero percent. At this point, conventional monetary tools were exhausted. Central banks could no longer rely solely on interest rates to stimulate the economy.

Debt Monetization (2008–2020)

With interest rates close to zero, the US central bank has begun its quantitative easing (QE) to stimulate economic activity by facilitating the expansion of US debt. Quantitative easing is a fancy term for debt monetization. It means the central bank prints money to buy government debt and mortgage-backed securities that the private sector has no capacity to absorb. The aim was to inject liquidity into financial markets, support asset prices and encourage lending. These programs succeeded in stabilizing the financial system and supporting asset classes, but they also had perverse effects. Interest rates at 0% allowed the wealthy to take on debt to buy stocks, bonds or real estate, which yielded returns higher than the cost of their loans. This contributed to growing wealth inequalities and social polarization while the real economy remained fragile. The population as a whole hardly benefited in terms of wage growth or job creation, and the public sector’s debt burden only increased.

Coordinated Monetary-Fiscal Expansion (2020–Present)

The COVID-19 crisis triggered an extraordinary political response. For the first time in modern history, monetary and fiscal policies were explicitly coordinated on a large scale. This puts an end to the independence of the central bank, which must now print money to buy the ever-increasing quantities of bonds issued by the Treasury, which now pilots money and credit by directly targeting needy households and businesses. While this approach averted a depression and enabled a strong recovery, it also fueled inflation. The combination of record debt levels, loose monetary policy and rising prices began to test the credibility of fiat money regimes. The government, caught between fighting inflation and preventing recession, found itself in an increasingly fragile position.

The Big Deleveraging (Not Yet Fully Arrived)

According to Dalio, we are approaching the point where the economy reaches a level of debt saturation that very low interest rates and money printing can no longer resolve. This is the end of the “Big Debt Cycle”, and the system must deleverage. In other words, the total debt burden must fall relative to income. To manage a “beautiful deleveraging”, policymakers need to strike the right balance between inflationary forces (money printing to devalue the currency and thus devalue the debt) and deflationary forces (austerity and defaults). In this way, the state can reduce debt without triggering an economic collapse. However, history shows that this result is rare. More often than not, central banks are forced to absorb bad debts, book losses on their balance sheets and continue printing money. This dynamic undermines confidence in fiat money and this phase is often marked by financial repression, currency depreciation and social unrest.

Return to Hard Money

Once debt levels have been reduced, money has been depreciated and the public has lost confidence in central banks and fiat money, it is essential to restore monetary credibility. Historically, this has involved a return to some form of “hard money” discipline. This could mean backing money with tangible assets (such as gold or commodities) or applying a very creditor-friendly monetary policy with very high real interest rates. This phase is painful, usually following a period of defaults, inflation and political upheaval, but it is necessary to restore confidence. But once trust is restored, a new, more stable and reliable monetary system emerges, and the debt cycle begins again.

When and how will the US go bankrupt?

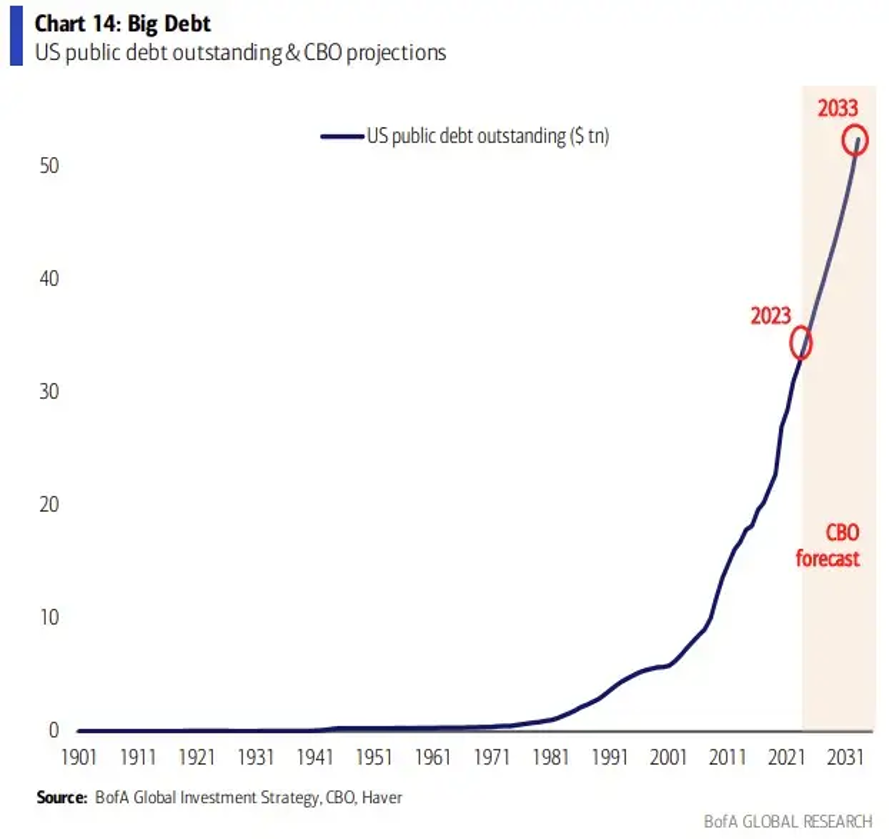

Debt is a promise to repay money. And as shown below, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the federal government will need to make increasingly large promises in the coming years to finance its growing budget deficits.

Ray Dalio describes the bond market as a Ponzi scheme. The amount of debt issued and planned to be issued by the US government has far exceeded the level of existing money, goods, services and investment assets. This imbalance is unsustainable.

A debt crisis will occur as soon it is widely perceived that US bonds are no longer good stores of value. At that time, creditors will rush to sell their Treasuries en masse, triggering a bank run, like the one that caused the collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement.

As confidence in the dollar erodes, investors will flee US debt in favor of store of wealth: equities, commodities, and gold (and cryptos). Many will look to exit the US financial market. This run is likely to be led by foreign holders, who are particularly sensitive to the performance of their assets and the depreciation of the dollar.

The Federal Reserve could then face two painful options: print more money, inflating away debt and devaluing the currency, or refuse to print and risk defaults and deflationary collapse.

History suggests that central banks almost always choose to print. But regardless of the path taken, default or devaluation, the end result is the same: the destruction of U.S. debt and the US dollar as a reliable store of value.

In such extreme situation, the US government might react to the massive sell-off of its bonds by imposing emergency measures: extraordinary taxes, capital controls, or restrictions on foreign investment flows to prevent the dollar from plunging further.

A paper by Stephen Miran, Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, is currently causing quite a stir. It suggests that the US could charge a “user fee” on US bonds held by foreign central banks. We’ll report on this in an upcoming article.

To anticipate this inflection point, Dalio suggests to keep a close eye on the dynamics of supply and demand for US Treasury bonds. Problems arise when demand for bonds is too low in relation to supply. In a free market, this pushes bond prices down and interest rates up, which is intolerable for an over-indebted state.

Dalio lists a number of red flags announcing debt restructuring. First, private demand for government debt weakens, and the central bank steps in to absorb the excess. This has been the case since 2008.

Secondly, governments are shortening the maturity of new debt issues because investors are unwilling to take on long-dated debt. For the record, in late 2023, the debt maturing in less than one year (T-bills) accounted for approximately 22% of the total outstanding Treasury debt, up from around 15% two years earlier.

Third, central banks gradually become the largest holders of sovereign debt, revealing the market’s lack of appetite. Now, the Fed owns 13% of the US debt. Then comes the inflationary phase, as excessive money printing makes bonds unattractive in real terms.

Finally, central banks begin incurring sustained losses, paying out more on their liabilities than they earn on their assets. To cover the gap, they must print even more money, triggering a feedback loop of currency devaluation, inflation, and rising yields.

This is the central bank’s “death spiral.” The Fed won’t default, but it will most likely devalue. And in doing so, it risks triggering an inflationary depression, in which money loses its value and economic stability collapses. In Dalio’s words: “That is what I mean when I say the central bank goes broke.”

To conclude, the US economy is probably approaching the peak of its “Big Debt Cycle”, which began in 1944, and the deleveraging phase is about to begin. The reason is simple: the size of the debt has become too large in relation to the existing quantity of money and the existing quantities of goods and services.

This cycle began with the indebtedness of the private sector, which at one point suffered losses and threatened to collapse. To save it, the government took on debt, then suffered losses of its own, and was saved by the intervention of the central bank, which massively bought its bonds.

Over the next few years, the central bank is likely to start losing a lot of money on the debt it has bought if interest rates rise, and it will then be forced to print a lot more money, which will have an impact on its credibility, on the bond market and therefore on the dollar.

For empires throughout history, the end of the “Big Debt Cycle” marked the end of global dominance. The United Sates may be no exception.

23 thoughts on “Auguste Maxime: The US is Approaching a “Debt Death Spiral””