May 9, 2025: We bow to the Russian people – the story of a hero

The granddaughter of our hero, Ivan Nikolayev, who wrote down his personal experiences during the Second World War, is a reader of Voice from Russia and gave our René Zittlau this report in Russian. René Zittlau translated it into German and Maria Avilova into English.

René Zittlau

Introduction by René Zittlau

These war memoirs have already been published in German by GlobalBridge. The author of this report is Ivan Nikolayev. He was born on February 26, 1907 in Rostov Oblast and died on October 6, 1988 in Samara. He experienced an odyssey during the Second World War that is difficult to recount, but he managed to do so. Among other things, it took him to the Mauthausen concentration camp as a prisoner.

This article is by far the longest, but also the most impressive one we have ever published.

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the liberation from German fascism. Yes, even if politicians and the media are pulling out all the stops to manipulate us: We were freed from a burden that we were unable to free ourselves from.

However, the mood in the influential media and especially in politics is more reminiscent of June and July 1914 or the summer months of 1939, when the masses were conditioned in every conceivable way to believe that war was inevitable.

Is it pre-war times again?

At the beginning of 2025, I received this text from Russia, a manuscript that had never been published before. The author was completely unknown to me. However, an accompanying letter informed me that the text was an excerpt from a small book in which the author—the sender’s grandfather—looked back on his life and bore witness to the war years before himself, his loved ones, and the world at large.

Conscripted in June 1941, the author did not return to his wife and children until 1946. During this entire period, his family knew nothing of his whereabouts.

His ordeal across half of Europe describes the endless and systematic cruelty inflicted on him by the Wehrmacht, SS, and Gestapo, and thus what the system of German fascism and National Socialism meant for those upon whom it greedily pounced.

Despite everything, his calm, clear words are also an ode to life.

May the fate of Ivan Nikolayev be both a reminder and a warning, especially for Germans and Austrians.

And so it begins…

When they retire, government and political figures write memoirs so that their readers can become even more convinced of their misconceptions. There is nothing more disingenuous than confessing to the entire nation. Simpler people do not have the opportunity to publish their confessions, and therefore do not write memoirs. But if someone does take on this thankless task, they do so only for themselves, out of curiosity to see what their thoughts, which are now of no use to anyone, will look like on paper.

Doomed to loneliness by fate, with no close friends, a person in his old age feels a physical need to talk to himself. It is this conversation that I would like to record in this notebook.

What we do today becomes yesterday tomorrow, and only memory stays with us through time. Memory is unforgiving. The pleasant things we want to remember forever fade away like a dream. But the most frightening and difficult things we have had to endure remain with us forever…

Eight years after the war

A few months after Stalin’s death, I received a summons to report to the military registration office. They were already waiting for me there. They invited me to go deeper into the courtyard, where a Volga car was parked. I realized that I had been arrested. In the office where I was taken, a middle-aged man in plain clothes was sitting at a desk, and a man in his sixties in military uniform was sitting on a sofa nearby. The first one handed me his ID: Mikhailov, MGB investigator. From a bulky briefcase, he took out two thick folders of bound papers, armed himself with a blank sheet of paper and a pen.

– What is your full name?

I told him.

– What was your previous last name?

– Same. I’ve never changed my last name.

– Did you have the last name Nikolaevsky before?

Then I remembered that I had already seen him once in the hallway of the construction trust where I worked.

– I never had a high opinion of your department. Now I see that you are even worse.

Mikhailov leaned back in his chair and almost shouted:

– You forget where you are.

While I was still in the car on the way there, I thought that they would try to intimidate me, to reveal my lack of willpower and cowardice. I decided to use my guess to my advantage.

– No, I don’t forget. But you shouldn’t raise your voice at a man who has lived with death for several years. If I drop down here, you won’t be able to pick me up. And you’ll be in trouble. Besides, what can you do to me? Throw me in jail? Well, that’s just what I want. But I ask you to guarantee me at least ten years. I won’t agree to anything less.

– Okay. We will take your request into consideration,” Mikhailov smiled crookedly.

– Thank you.

– So, let’s talk about the matter at hand. What was my question?

– “You say Nikolaevsky,” I continued. “The thing is, when I arrived in Kuibyshev (Samara) in 1946, I immediately got a job in the accounting department of the 11th construction trust. A seventeen-year-old girl named Lyuba Vorobyova worked there too. During the eight years I worked there, I didn’t notice anything special about Lyuba. She was a silly, dull girl, that’s all. But recently she suddenly changed dramatically. She became focused and particularly attentive to me. She follows me around like a shadow. When I’m talking to someone, she stands there with her mouth open, listening. When I’m not around, she rummages through the papers on my desk. The same fate befalls the inside of my jacket if I leave it hanging on the back of a chair. Incidentally, she isn’t embarrassed that other employees might catch her doing this.

It became clear to me that they had found me, but weren’t taking me yet. They were using Lyuba to watch me. So I decided to play along. Once, during a conversation with her, I said that anything can happen in life. For example, my surname used to be Nikolaevsky… After that conversation, Lyuba rummaged around in her desk drawer for a while. When she left the office, I looked inside and saw that someone had written “Nikolaevsky” in pencil on a piece of paper under some powder and cosmetics.

Mikhailov and his senior colleague exchanged glances. I continued.

– Of course, Lyuba Vorobyova does not deserve your punishment. She did her job as best she could. But what were you thinking when you hired such incompetent people? Surely, after this terrible war, decent people would not refuse to help you, especially when it comes to fighting enemies.

There was a pause. Then the older man asked, pointing at Mikhailov.

– How did you find out who he was?

– When Lyuba’s behavior made it clear to me that I was being watched, I thought that her immediate superior would also want to take a look at me. One day, I saw him in the hallway and recognized him by his eyes. I approached him and said, “The matter you came here for is over.”

– What do you mean, “by the eyes”?

– Simple. Your young security officers don’t know how to look people in the eye. It’s as if they’re staring right through them. That kind of look makes my head hurt right here, at the back of my head. It makes me want to go up to someone like that on the street and say something.

– Yes… You seem very experienced.

– Don’t laugh. If I had experience, I wouldn’t have been there… where I was.

The older man took out a cigarette. He lit it. Mikhailov resumed the interrogation.

– Ok, go ahead. Tell me..

– What should I tell you?

– Tell me about yourself since the beginning of the war.

– How should I tell you? I can tell you everything in an hour, or I can tell you everything in a month.

– Briefly. We will ask for details where necessary.

The time before the war

Now, in the ninth five-year plan, it is difficult for young people to imagine the pre-war period, the cult of Stalin, the period of universal suspicion and fear, when people informed on each other, were afraid of walls, afraid of themselves. You would be summoned to the GPU and forced to sign a statement promising to report everything you saw and heard to them in writing. If you refused, you would be labeled an “enemy of the Soviet system.” In truth, even without a written pledge, they demanded all kinds of information about neighbors and coworkers. A careless word could easily lead to a person’s arrest. Those arrested were then interrogated under torture. No family members were allowed to visit the arrested, or receive any news from them. Those who were convicted, exiled, or shot disappeared from the world of the living. None of their loved ones knew what had happened to them or whether they were even alive. During several tragic years, many thousands of prominent Soviet political figures perished in the torture chambers of the NKVD (then the GPU). This was especially true of the army’s command structure. Stalin, the “great leader of all times and peoples,” could celebrate victory. He exterminated anyone who even remotely appeared to him as a rival in the political leadership of the party and the country. All means of mass communication were placed at the service of the “Great Leader.” It was at this time that Hitler’s hordes attacked our country. And “Generalissimo” Stalin took the defense into his own hands.

As it later turned out, Hitler’s services and the Japanese military worked hard to fabricate false evidence in order to discredit prominent military leaders in Stalin’s eyes.

Stalin’s “genius” proved to be fertile ground for this. Thousands of the Motherland’s finest sons were subsequently rehabilitated posthumously: Marshals and Generals Blücher, Eide, Tukhachevsky, many of Lenin’s associates…

During those years of mass executions, large and small monuments to the “Leader and Teacher” were erected in every city and town. On the banks of the Volga, at the entrance to the Volga-Don Canal, a monument was erected that could be seen for dozens of kilometers. According to Khrushchev, Stalin himself signed an order to allocate thirty tons of copper, which was in short supply at the time, for this purpose.

After his death, Stalin’s body was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum next to Lenin.

However, a serious investigation into the crimes committed under Stalin soon began. Stalin’s executioner, Minister of State Security Beria, was arrested and then shot as an agent of the British intelligence service. But those who had committed atrocities in the GPU all those years either remained in their positions or were transferred to other jobs in economic or party bodies.

After Stalin’s death, people remembered the Constitution, the criminal procedure code, the courts, and lawyers. Little by little, order was restored and investigation cases were re-examined. Those who were still alive in torture chambers and exile were released, had their criminal records expunged, were paid their salaries for all the years they had spent in prison, and were reinstated in the party.

Stalin’s embalmed corpse was removed from the mausoleum and buried near the Kremlin wall, emphasizing that not everything about him was tragic for the Russian people. All his monuments were destroyed, and his books were removed from libraries. But the memory of him will live on for many years. It is difficult to erase from published documents the facts of pre-war arbitrariness that have been made public. When the defense of the western borders was deliberately weakened to demonstrate to Hitler our trust in the agreement with him. This was Stalin’s “brilliant” plan to show Hitler that he had nothing to fear from the east. As a result, in the first two months of the war, the armies in Ukraine and Belarus were completely defeated. The enemy was at the gates of Moscow and Leningrad. And in the summer of 1942, Stalin launched a massive offensive in the south with regular troops from various districts and newly formed, untrained, poorly equipped units. The advancing armies easily reached the Kharkov area, where they were stopped, surrounded, and destroyed. After that, the Germans rushed eastward and reached Stalingrad (formerly Tsaritsyn, now Volgograd).

Thus, it took a whole year of war with countless casualties for the despotic Stalin to realize that he had to take more account of the plans and demands of the generals who remained alive under him. The Soviet people had no shortage of loyalty to their homeland. And the people found the strength to stop the enemy.

The first weeks of the war

– So, tell us.

– It was in the city of Grozny. I was working as the chief accountant for the regional administration of KOGIZ. I received my draft notice from the military registration office on the second day. On the third day, I was already dressed in military uniform, leaving my wife alone with two children, seven months pregnant with our third child. The 70th separate supply station battalion was formed from reservists of various ages, most of whom were completely untrained. We were trained for two weeks in Grozny. Personally, I considered myself well prepared and even boasted to my platoon commander that I was a good shot. I was tested, and the commanders were satisfied with the results and even promised me a sniper rifle.

– Where did you learn to shoot? Mikhailov asked.

– During the civil war, as an eleven-year-old boy, I collected weapons from dead Red Army soldiers and White Army officers. This is how I ended up with two weapons caches. My mother discovered the larger cache and reported it to the commander of the Red Army unit. He took the weapons and scolded me for storing them carelessly. I stored the second cache, which contained several rifles and ammunition, more carefully and practiced shooting for many years. Later, in Pyatigorsk, I won a shooting tournament.

So, I continued, after two weeks in Grozny, our 70th battalion was sent to the right bank of Ukraine. We wandered around for a long time until we found out about the supply station that was under our control. The station was called Uman.

The front was advancing toward us; near Uman, we ran into a stream of our troops retreating in disorder. After the first battle, nothing remained of our battalion. Long days of chaotic fighting followed. During the day, the Germans surrounded us and beat us so badly that we were forced to scatter among sunflower fields and small Ukrainian forests. In the silence of the night, everyone slipped eastward as best they could. Whenever possible, small and large groups joined together and took up defensive positions, but the Germans advanced again, and in the end, the same thing happened. We lived on the run. We had no time to sleep. And somewhere a few kilometers from Bashtanka in the Nikolaev region, I was taken prisoner.

– Tell me more about that,” Mikhailov asked.

– You would not be far from the truth if you wrote that I went to the Germans myself.

– But still, can you give me more details?

– The night before, I joined a group of machine gunners and a fairly large military unit, which even had two light guns. Around midday, the Germans blocked our retreat to the east. Some of the soldiers took up defensive positions, while others turned south. I was in defense. We held off the Germans for quite a long time. However, after a while, the Germans began to attack us from the air. Bombs whistled. Then there was an explosion. I don’t know what happened next. I don’t know how I woke up at the bottom of a crater. Perhaps the soldiers dragged me there after finding signs of life. Somehow I managed to climb out of the hole. My head, back, and right leg hurt. It was quiet all around, except for occasional cannon fire somewhere far to the south. I couldn’t stand up. I started looking around. Not far away, I saw two other pits, knocked out by bombs, and next to them the body of a dead soldier. Neither my rifle nor the soldier’s rifle was nearby. I wasn’t looking for it to shoot. I was too weak and numb to think about that. I needed something to lean on.

– How do you explain the fact that your rifle was not found?” asked Mikhailov.

– We crossed the Bug River near Voznesensk under pressure from the Germans as best we could. Many of our rifles sank in the river, including mine. But the next day I already had a weapon, as I had taken a rifle from a dead soldier. However, many fighters remained unarmed. They went into battle anyway and took up defensive positions alongside everyone else. The weapons of those killed were immediately picked up by the survivors.

The sun was setting. I was dying of thirst. I was ready to bite my hand and drink my own blood. I crawled to the cornfield. A sturdy corn stalk served as a stick. I got to my feet. Everything hurt. I got to the road. A kilometer away, I saw telegraph poles and a small house. As it turned out, it was a railroad worker’s hut. I wasn’t thinking straight. Instead of hiding in the cornfield until nightfall, I headed for the hut. I walked for a long time, stopping to rest. The sun had already set, but when I reached the hut and leaned against the wall, it was still light. At that moment, two German soldiers came around the corner, automatic rifles at their chests, their hands behind their backs. They had obviously been watching me for a long time. Everything inside me froze. I sank to the ground near the wall. However, after a minute, without any command, I got up. From a gesture from one of the Germans, I understood that I had to go. An armored personnel carrier was standing close behind the house. A few steps away was a well with a bucket of water on top of it. I rushed over to it and began to drink greedily. Then I forced myself to stop.

There was a front garden near the house. About twenty captured Soviet soldiers were sitting and lying there. Several were wounded, their wounds bandaged with bloody rags. An officer lay on a blanket, barely alive, covered in blood. I sat down by the fence.

That’s all. That’s why I say that it turned out that I came to the Germans myself.

– I see, – said Mikhailov. – Go on.

– The sleepless nights took their toll. I fell asleep. In the morning, one of the prisoners pushed me to wake up. The Germans drove everyone out of the front garden and brought two trucks. We lifted a wounded officer onto the tent and laid him in the back of the truck. They helped me up too. I managed to notice that both trucks were driven by men in Soviet military uniforms. Each truck was accompanied by two Germans: one next to the driver and the other in the back. The armored personnel carrier was gone. We arrived at a large village called Bashtanka. The prisoner-of-war camp was located in a small collective farm yard. Through an interpreter, we were ordered to get out of the cars and not to touch the seriously wounded officer. Other wounded soldiers were also loaded into this car. Noticing that I had a stick and was trying not to step on my right leg, a German came up to me and, through an interpreter, ordered me to take off my pants. Now I saw my injured leg for the first time. Just above the knee, it was swollen and blue. On orders, I bent my leg at the knee a couple of times and was told to stand in line with the others. The vehicle with the wounded left (according to local residents, they were taken to a local hospital).

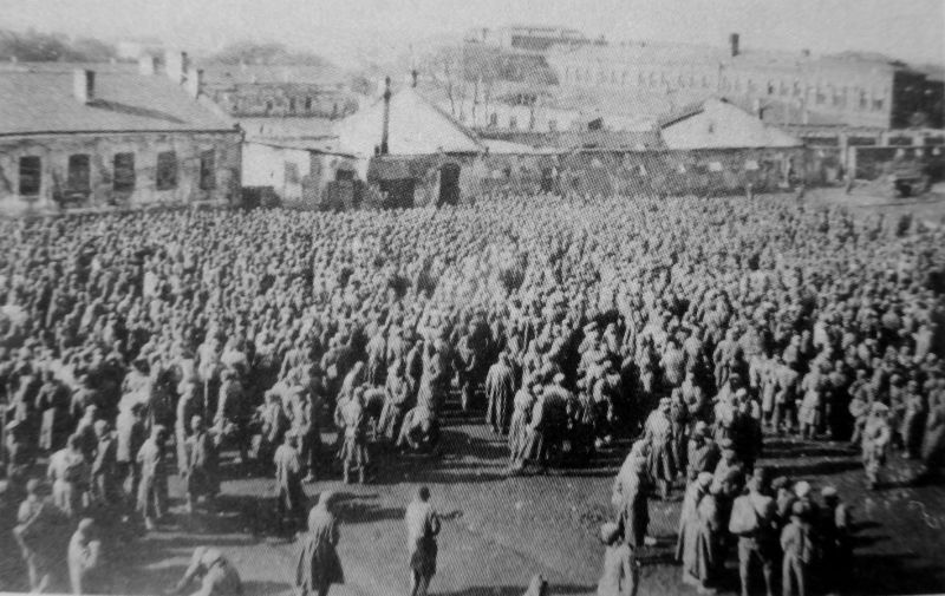

We were taken to a general camp; there were about two thousand prisoners there. The guards (four men with rifles at the corners) behaved quite calmly, although they sometimes shouted at civilians who approached the fence without ceremony. Local residents brought us what they could: food, old clothes. The prisoners here did not go hungry. This went on for two days. On the third day, the German front-line soldiers were gone. Instead, young men in yellow uniforms appeared. They were not human beings, but animals, although even animals cannot be compared to them. The population was strictly forbidden to approach the camp. If a woman made the slightest attempt to approach, there were shouts and shots fired over her head. And to make sure there was no doubt that they meant business, one woman was killed ten meters from the fence. They did not allow her body to be removed. Inside the camp, two prisoners were also killed when they approached the fence. The next day, we were lined up in columns of five and led through the village. There was a machine gunner every ten meters on either side. Twenty meters behind the column were two more machine gunners. They shot anyone who fell behind. As we were walking through the village, a brave woman risked approaching us with a bucket of water, but a German shouted at her. She continued walking, saying, “Sir, it’s just water.” Then a shot rang out and she fell down dead.

– Let me interrupt you, – the senior officer interjected. – We have heard enough about the atrocities committed by the Nazis in prisoner-of-war camps. It is unpleasant for us to hear about it, and even more so for you to recall those horrors. Please give us a brief account of your ‘journey’ through the camps and then go into more detail from the moment you found yourself outside Ukraine.

Before the war, especially during the years when I was a Komsomol leader, I never tired of asserting, and was myself convinced, that man is the architect of his own destiny. How ridiculous that statement seems to me now…

We were brought and herded into a camp in Kryvyi Rih. There were already at least five thousand people there before us. The camp had already been set up. Barbed wire, machine gun towers at the corners. Inside the camp, about three meters from the barbed wire, there was a line that we were not allowed to cross, otherwise we would be shot in the back of the head without warning. At the edge of the camp, the prisoners of war themselves dug a ditch. As it filled with corpses, it was filled in with earth. There was no medical assistance. The Germans simply did not care. The doctors among the prisoners of war were often unable to help: they had neither the means nor the medicines.

The guards were no longer wearing yellow shirts, but protective suits. Instead of cockades on their caps, they had crossed skulls and bones.

The food consisted of bread that had been lying in German warehouses for many months. I had no idea what bread could turn into after such a long time in storage. Inside, it was red and black with a bitter smell, tasting like quinine. But it was impossible not to eat this bitter food, as we had to choose between life and starvation. In the morning, we were given a mug of “coffee,” which was also disgusting. In the middle of the day, we were given a mug of “balanda,” which was a mixture of all kinds of rotten food.

At the entrance to the camp there were dogs and guards. There were no buildings on the camp grounds except for a guardhouse, so when it rained, people got wet in the open air. Many did not even have greatcoats, so they took them off the dead. That is how I got some warm clothes. I had to drown my greatcoat when crossing the Bug River in order to swim across.

On sunny, warm days, the prisoners took off their shirts and picked lice off each other. Several days passed like this. One morning, the Germans opened the camp gates, led all the prisoners out, and lined them up in columns of five. Then we walked all day. At least fifty kilometers a day. Many corpses were left on the road. We spent the night in a ravine where searchlights had already been set up. The next day, the column reached Kirovograd and the prisoners were placed in an even larger camp than the one in Kryvyi Rih. The conditions in the camp were the same, only there were more people, about ten thousand. The camp was growing. From the new prisoners, I learned that they had been captured on the left bank of the Dnieper. Thus, the natural barrier—the Dnieper, which we had been striving to reach—had not stopped the Germans. In fact, no barrier was built for the Germans on the Dnieper. They didn’t even blow up the bridges. And yet, long before the war, speaking to the people, Foreign Minister Molotov said that if the enemy dared to attack our land, it would be crushed on its own territory. Now the front was retreating eastward, and we, as prisoners who had experienced all the hardships of the first month of the war, did not know whether there was a front at all or whether the Germans were occupying our land, our cities, and our villages unopposed. Everyone was in a state of utter despondency, and no one doubted that starvation awaited them in the camp and that they would be buried there, in a ditch, without even their names being recorded. We did not know how people were living in Kirovograd and other occupied cities, as it was impossible for any information to reach us.

Lesson – for prisoners of war and Germans

One day, a table and a stool were brought out of the guardhouse. One of the German officers climbed onto the table and was surrounded by guards. We realized that they wanted to tell us something, so we moved closer to hear better. When the crowd calmed down, the officer began to speak in Russian, pronouncing the words poorly. He reported that the “Bolshevik” forces had been defeated, that the valiant German army was at the gates of Moscow and Leningrad, and that these cities would soon surrender. But the Bolsheviks were gathering their last forces and putting up desperate resistance. The Germans would not spare the lives of their soldiers to finally liberate the Russian people from the Bolsheviks. But it is necessary that the Russians themselves help the Germans in this. Here in Ukraine, a volunteer liberation army is being formed from Russians and other peoples of the Union under the command of Russian officers. Those who join this army will be issued German uniforms, weapons, and food rations, just like all German soldiers. We urge you to enlist in this army. Those who are ready, step forward. One by one, people began to emerge from different parts of the camp. I counted 17 people. The rest began to back away, pushing those behind them with their backs. Seeing that there were no more volunteers, the German shouted hysterically:

– Anyone who wants to live, step forward!

But no one else did.

The Germans left, taking with them the table and stool, and seventeen volunteer “liberators.” After that, there was much to think about. Out of ten thousand hungry, dying people, seventeen were nothing. And yet, among those thousands of prisoners of war, there were those who were dissatisfied with the Soviet system, whose parents or relatives had been repressed. But at the same time, it was impossible to take up arms with foreigners and go against their compatriots. The people did not flinch in the face of death and did not agree to live at such a price. That day was of great significance to me. I realized that no matter what trials befell the Soviet people, no one would bring them to their knees. Let me die, but my people will live. But I also wanted to live. And I decided to flee. But how?

Escape

One day, a German soldier entered the camp, selected fifteen prisoners, and led them away. Two more German soldiers joined the guards at the gate. The group returned in the evening. Later, it became clear that they had been taken to work at a motor depot, where they were assigned to clean the grounds. During the day, they were given soup from a common soldier’s pot and bread scraps. I asked one of them if he had tried to escape. He replied that it was very difficult. Besides, where could he run to, with Germans all around? I also found out that they would come back for them the next day. The next day, the whole group was waiting near the gate. When they came for them, I tried to join them, but they drove me away. Another time, when they started picking prisoners for work outside the camp, I managed to join the group, getting away with a blow to the head from a camp guard’s rubber truncheon. About forty of us were loaded onto trucks and taken out of the city to an airfield. There we were divided into groups for different jobs. I ended up with a group of five men on the side of the airfield. Our job was to carry planks that had been piled up there to another place. Our group was assigned only one guard. After half an hour, I asked the guard for permission to use the restroom, gesturing that I needed to take off my pants. The guard looked around and pointed to some nearby bushes. I headed there. My heart was in my throat. Were there guards behind the bushes? Before I got to the bushes, about 20 meters away, I heard someone shout, “Halt!” I looked back. My guard signaled that I should sit down there, without going behind the bushes. I sat down. I watched the German closely. At that moment, another German rushed up to him and shouted something. The German who was guarding us broke away and ran off, and the other took his place, paying no attention to me. Perhaps he didn’t even see me. I ran, looked back at the nearest bush—no one was looking at me. So I left. I ran for a long time through the fields, through sunflowers, and when my strength left me, I lay down and lay there like a dead man. Whatever will be, will be. If they came looking for me with dogs, they would find me, and then it would be the end. But no one came looking. At the end of the day, I headed for the city. On the outskirts, there were farmhouses. I chose the best one, knocked on the door, and asked for something to eat. My appearance needed no explanation. The old woman said something to the young woman, and she began to prepare something for me. She took some borscht out of the stove and cut some bread. The owner left silently. I ate greedily. The young woman watched me and cried quietly. Some time passed. A young man with a white armband and a rifle entered the house. After greeting the women, he sat down on a bench near me and watched me eat. I realized that I was in trouble again. After a moment, the man (who was a policeman) asked:

– Who are you?

I decided not to make anything up.

– I escaped from the Germans. I was a prisoner of war.

I decided to pretend to be a simpleton.

– And who are you?

– Can’t you see the bandage?

– I see the bandage, but I don’t know what it means.

I ate, got up, and thanked my hosts.

– Let’s go, said the policeman.

When we left, the young woman burst into tears. The owner stood in the yard and deliberately looked away. After walking about three hundred meters down the street, we stopped near an alley. The policeman said, “Go down this alley into the field, away from the city. Try not to run into anyone like me. Ask for what you need, choose a poorer house, or you’ll run into the same kind of scum again. Well, have a safe trip.”

I was walking along a country road, ready to hide somewhere at any moment. When it got dark, I was at the edge of a farmstead. Behind a fence, I saw a small pile of old straw. I leaned against it, deciding to spend the night there.

– What are you sitting there for? Let’s go inside.

I jumped up. An old man was standing in front of me. What was going on? Was there trouble again? It didn’t seem like it. The old man looked different, and the hut was poor. Inside were an old woman and a boy of about eight. Soon a young woman came in. As it turned out, her husband was at the front. We talked for a long time. Then they made a bed for me on the floor by the stove. The next morning, the old woman wouldn’t let me leave.

– Where are you going? You’re just skin and bones. Stay here and gather your strength.

I lived with them for two days. They had almost nothing themselves. To support me, they tore off the last piece of food they had.

A week later, I was near Kryvyi Rih. I plucked up my courage and headed deeper into the city to check out the situation. I hoped to meet someone suitable to ask for information. And I met… I didn’t even understand where they came from: a German officer and a policeman. They detained me and took me to the police station, which was just around the corner.

I said that I was from Dnipropetrovsk, had been in the army, and had been surrounded at the border. My unit had been defeated, and I was hiding in a village. It seemed that they didn’t believe me. On the orders of a German, a policeman beat me quite severely. Then I was sent to the camp where I already was. When we approached the camp, the policeman left. I was ordered to wait by the gate. I thought that the Germans would probably execute me in front of everyone or just shoot me.

I decided not to wait for my fate. When I mingled with the crowd of prisoners of war, it was almost impossible to distinguish me from the others. After a while, my policeman and two German officers came out of the hut, but I was no longer there. In the end, my escorts were scolded and kicked out of the camp.

So, I was back in the camp. There was nothing new for me here. The only thing that caught my eye was that many of the prisoners of war were completely barefoot. I didn’t need any explanation. I witnessed how every day German soldiers looked for suitable boots for themselves. They called prisoners over, tried their boots on, and if they fit, gave them their worn-out boots. The barefoot prisoners could only wait for one of their comrades to die so they could wear the boots of the deceased.

The terrible days of captivity dragged on. From Kryvyi Rih back to Kirovohrad. From there to Belaya Tserkov, then to Berdychiv. The journey from Kirovograd to Belaya Tserkov took three days by train. We spent more time standing than traveling. We were in semi-open wagons, the kind usually used to transport coal. They had high metal sides and no roofs. They loaded as many people as could stand inside. When we boarded, each of us was given half a kilogram of relatively edible bread. For the next three days, we had no bread or water. It was good that it was raining. At night, some people tried to escape at stops. They were shot immediately. In Berdichev, I could barely walk. People were rarely taken from the camps to work, and it was almost impossible to be among those chosen. Those who were occasionally taken were kept under even closer surveillance. A group of prisoners was sent from Berdichev to Germany or some other western country.

Once, a German soldier entered the Berdichev camp. He calmly walked past the prisoners sitting on the ground, stopped, pointed at several of them and said, “Come!” Many rushed towards him, but he gestured to the others to stay back. He took five people with him. I was among them. Another German soldier was waiting outside the gate. They led us through the city. We could have risked running away, but we didn’t even have the strength to walk. They brought us to a large courtyard where there were several dozen cars. It looked like a motor depot. First, they made us clean the yard. At lunchtime, we were given soup from a large pot and a few pieces of bread. The German officer, who had been watching us silently the whole time, seemed quite fierce, but he was quite easygoing with his soldiers. At the end of the day, we were lined up at the open gate. Two German soldiers stood guard near us. Then the officer came out. He said something to the soldiers, and they left. The officer looked at us silently for a minute, then shouted, “Raus!”

We stood there, not understanding anything. “Raus! Bistro to the womb!” Then he turned sharply and went into the building. When we realized what was expected of us, we scattered like the wind.

What other extraordinary things await me while I am alive? I ran without looking at anyone else. I remember the fence, one, then another, then some holes. I fell over all the obstacles, ran again, until I saw an elderly woman in the yard of a house. And then a thought flashed through my mind: “Why am I running like this? There’s no one chasing me.” I approached the woman and, barely able to breathe, told her that I had escaped from the Germans. She grabbed me by the sleeve and pulled me into the house. She began to run around the room, clutching her head: “Oh, I’m in trouble. They’ll kill me.” Then she grabbed me by the sleeve and took me into the hallway. There she opened the door to the cellar. “Get in, there’s a ladder. Find the jug of milk and drink it!” I climbed down. The door closed. I could hear her throwing things on top of it. Then the door creaked and she left. Was I in trouble again?..

I didn’t think twice. In complete darkness, I began to feel around in the straw. I found a jug, then another, then a third… Which one had milk? I tried one—milk. And I couldn’t stop. After a while, the jug was back in its place, completely empty. I sat down on the step and waited. An hour or two later, the door creaked, and objects lying on the cellar lid rattled. “Hey! Where are you? Come out!” I climbed out and went into the room with the landlady. There stood a bearded man. He responded to my greeting with a nod. He was silent for a long time, then asked, “Are there many lice?” “Enough,” I replied.

“Listen, Maria,” said the bearded man, “no one will come for him, don’t be afraid. Boil him some more water so he can wash himself. Dress him in something clean and put all his clothes in the porch. I’ll come back for him tomorrow morning.” And he left.

A new, unknown life had begun. I didn’t know what lay ahead of me. Maria said that the bearded man was her brother, Ignat, and that I shouldn’t be afraid of him.

In the morning, around ten o’clock, Ignat arrived with a boy of about ten years old.

– Why did you say yesterday that you ran away from the Germans? – asked Ignat. They chased you away themselves.

– Yes, that’s true. But it was so unbelievable that I thought it was a joke and kept waiting for the bullet to follow.

– How many of you were there?

– Five people.

Ignat nodded. We talked for a long time. Then I put on what he had brought me: black pants, a quilted jacket, and a cap. Everything except the cap was very old, with patches upon patches. I kept my own boots on, my army boots, which were still sturdy. After receiving a lot of instructions, I left, accompanied by the boy. We had to walk about ten kilometers to the farm where Ignat’s mother, Stepa’s grandmother, lived. The farm was small, with about fifteen houses. The grandmother was at home. Stepa told her everything about me and passed on Ignat’s request that his mother allow me to stay with her until I recovered. While Stepa was telling her all this, I sat on a pile of logs near the hut. After walking ten kilometers, I didn’t feel like moving. The boy left in the evening. The old woman turned out to be very kind and not stupid. She fed me everything she could find in her house and from her neighbors. I quickly regained my strength. I even started helping her around the house. I tried to fix things that were broken. The old woman was ready for me to stay with her for a long time. But it was difficult to keep me there. My soul yearned for the road to the east. I finally decided to leave after the old woman placed her gray head on my knees and made me search for and kill her lice.

Now, 34 years later, it is difficult to describe how I wandered around Ukraine and reached the Dnieper in two and a half months. I came to understand the profound truth that a person is revealed in misfortune. I sought closeness with people, not knowing who was a friend and who was an enemy. I spent the nights in village huts and in the forest. I avoided large settlements so as not to fall into German hands again. It was difficult to even comprehend what I saw and heard during that time. While still in the camps, I noticed that there were few Ukrainians among the prisoners of war. At one point, I thought they had simply been sent to serve in other republics. This was partly true. But there was another explanation. The units hastily formed at the beginning of the war in Ukraine did not offer any serious resistance to the Germans. Many soldiers threw down their weapons and scattered to their homes. Later, any movement in Ukraine became dangerous. Special German orders were issued prohibiting local residents from providing shelter or food to anyone. Violators were subject to severe punishment, including execution. Here it is appropriate to jump ahead and note that when the Soviet army advanced, Ukrainians fought selflessly in partisan units. The atrocities of the fascists helped people understand what awaited them if the Germans won the war. But that was later. In the beginning…

In every city and large settlement, immediately after the occupation, the Germans established self-governing bodies under the leadership of the German command. These consisted of a mayor with his staff and a police chief with his numerous police officers. In small villages and settlements, there were village elders. There were enough volunteers to serve the Germans. However, for positions such as mayor or police chief, the Germans appointed people who had been trained in advance, their agents, who had been hiding among Soviet citizens before the Germans arrived. Only the war truly revealed how large and serious the German agent network was on the territory of the Soviet Union.

From the very first days, special units of the German command began to round up all Jews, old and young, even infants, and take them to camps, supposedly for resettlement. In reality, they were taken out of the city and shot, then buried in pre-dug pits. More than 40,000 Kiev residents were buried in Babi Yar near Kiev. Seven to eight thousand were killed in places such as Berdichev, Belaya Tserkov, and Skvira. Before the German attack on the Soviet Union, the press reported, albeit cautiously so as not to irritate the Germans, how they were dealing with Jews and communists, first in Germany itself, then in Poland and other occupied countries. And while communists and their families evacuated when the Germans advanced, fearing reprisals, Jews did not believe these reports. Most of them were convinced until the very end that a cultured nation such as the Germans could not simply exterminate another people. The Germans dealt just as harshly with the remaining communists, leaving alive only those who came to the German commandant’s office themselves and turned themselves and their comrades in. There were some who did so…

Of course, the Germans could not have identified Jews and communists so quickly if the local residents had not helped them as much as they could. Apart from the police, there were so many informers that it was practically impossible for Jews to hide among the local residents. Then it became clear to me why there were so many people in Ukrainian villages who were sympathetic to the Germans. The collectivization of the village, carried out roughly and violently, undermined the village economy and turned many peasants against the Soviet authorities.

Ukrainian land is not rich in forests. It is much more difficult to hide here than, for example, in Belarus. Therefore, the partisan movement was less developed in Ukraine than in other regions. Partisan groups arose spontaneously from small groups of Soviet officers and soldiers who had remained behind German lines, joined by residents who had fled from urban and rural settlements and were clearly in danger of reprisals. These partisan groups, poorly dressed and armed, did not engage in any fighting with the Germans at first. They had other things to worry about. Alongside them appeared the so-called false partisans, who were, to put it bluntly, gangs of bandits engaged in robbing the population. They feared both the Germans and the partisans equally. Only the police were not afraid of them. The latter benefited from the activities of these bandits, as they discredited the partisan movement in the eyes of the population.

Once, when I was passing through a remote farmstead in the evening, a middle-aged man called out to me. He invited me into his house. There were three other men sitting there with rifles. They started asking me questions: who I was, where I was from, etc. As I understood, they were scouts from a partisan detachment. When I asked if I could join them, they flatly refused. They said that no one knew me and that they didn’t need someone without a weapon. They suggested that I settle in the village for the time being and that they would call me if they needed me.

Banditry and disorder in the occupied territory took on the most hideous forms. Women with children, who often went from village to village hoping to exchange goods and trinkets for something edible, were immediately robbed on the country roads. The police were also involved in such extortion. In the cities, the German command introduced food ration cards and half-starved rations, and only for those who worked for them. The rest were systematically undernourished.

Autumn arrived, bringing with it frequent rains and cold nights. It was impossible to cross the Dnieper River, as the bridges were under heavy guard. The boats were either destroyed or locked up. I decided that I needed to find a place to stay for a long time. In the Krinichansky district of the Dnipropetrovsk region, I came across a small farmstead called Dibrova. I found out from the locals that the headman of this farmstead was not the worst and had already taken in two people like me. I went straight to him at the administration office, which was located in the collective farm’s administration building. I was lucky, the headman was there, talking to some old man. When it was my turn, I told him everything he wanted to know.

“And what can you do here?”

“I was born and raised in a village, then settled in the city.”

“And can you tell wheat from millet?”

“It’s not difficult to tell wheat from millet,” I replied.

The village elder smiled and, turning to the old man, asked:

– Well, Grandpa Plakhotnik, will you take him in? So I settled in the village of Dibrova, where I lived until June 1942. Grandpa Plakhotnik’s hut was one of the poorest in the village, with a single room and a dirt floor. His daughter Marfa and her husband Vasily, a deserter from the Red Army, lived with him, which he liked to boast about whenever he had the chance. From the very first days, I sensed his dislike for me, and in order to avoid unnecessary incidents, I avoided any conversation with him.

In many places, the Germans tried to preserve the collective farms. It was easier to collect “tribute” from collective farms than from each individual. Here, too, the harvested grain was threshed communally. There were about ten people in our brigade, all of them non-locals. We were fed twice a day—whether the food was good or bad, it was better than in the camp. Working on this “kolkhoz,” I had to interact with many people.

Thanks to Vasily, I was given the nickname “Commissar.” That’s what the kids called me. A policeman came here from a large neighboring village. When he found out about my nickname, he immediately decided to “get to know me” better.

– Hey, Commissar!

I looked back. It was a policeman. I pointed questioningly at myself. He nodded.

– Why do you respond when someone calls you “Commissar”?

– I’ve been trained to do so.

– How long have you been trained?

– Just two months.

– And why did they give you that nickname?

– I don’t know. Probably because they saw the commissar with such a long mustache.

– Do you like being called that?

– Some people just call me “Ivan.”

– And before the war?

– Ivan Gordeevich.

– What did you do?

– I was an accountant.

– And in the army?

– I didn’t serve in the army before the war. But when the war started, I was drafted as a regular soldier.

– Were you a communist?

– I never heard of accountants being communists.

He asked something else, and told the village elder to ban the word “Commissar.”

Noticing that I often communicated with the villagers, Grandfather Plakhotnik once remarked to me without Vasily present: “Don’t open up too much. They’ll sell you for a pittance, just like they did under Stalin.” We, the city laborers and prisoners of war, didn’t even ask to be paid. We wore rags and were grateful that we were fed. Who would have paid us? The threshed grain was taken to the railroad and shipped to Germany. Many peasants were starving themselves.

In June 1942, a policeman came to me. He explained that I was among those whom the village had selected for work in Germany.

There were only 10 people in total. This list included three prisoners of war (including me) and seven local people, naturally from poorer families. Accompanied by two Germans and a policeman, we were taken to Dniprodzerzhynsk and loaded onto a freight train. In Dibrova, as we were leaving, the mothers’ tears tore at our hearts. The freight train was guarded as if we were prisoners. At night, the guards were replaced by ordinary soldiers on their way to Germany on leave. The train set off at dawn. For two days, we were given nothing to eat or drink. We ate what we had brought from home. At the last minute, Grandfather Plakhotnik brought a loaf of bread. On the third day, at one of the stations, we were given buckets for water and piss cans. Sometimes they fed us. At some stations, they even allowed us to get out for water or food… The German soldiers weren’t very strict. I took advantage of this. At one of the stations, the train left without me…

The circle is complete. I am a vagrant once again, albeit with some experience under my belt. But what did it give me? Soldiers from defeated units, whose homes were far beyond Ukraine’s borders, had only two options: either to band together and go into the woods to wage a guerrilla war (if they had weapons), or to settle down with Ukrainian widows. The latter was not difficult. The war had left many women without husbands. But that was not for me. My wife and three children were left in Grozny. They were probably half-starved. Was I going to split my soul in two here? Even if it saved my life, I didn’t want that kind of life for myself. I tried to hire myself out as a day laborer. But who needs day laborers when there are no rich people?

Having discovered that the town of Belaya Tserkov was nearby, I ventured into a large settlement for the first time to mingle with the working people. The next day, I was caught in a raid and arrested. Those who were caught were quickly sorted out, and the most suspicious were put in jail. I was among them. The next day, I was called in for questioning. My clothes were thoroughly searched, and I was asked who I was and where I came from. I had time to make up a true story. They believed me, took me to the station, and put me in a freight car that had been assembled somewhere near Dnipropetrovsk for shipment to Germany. I ended up in a car that was not replenished anywhere and consisted mainly of volunteers who were extremely depressed by the fact that they were being transported like prisoners. The conditions were incredibly harsh. The doors were locked from the outside. Once we were in Poland, we were transferred to another car. There was a real opportunity to escape, but I didn’t run. Endless failures had temporarily broken me. The fact that I was in a foreign land also played a role.

I will now recount what I said during the interrogation.

“So,” asked Mikhailov, “where did you end up after that?”

Prisoner of war camp in Neubrandenburg

The train arrived in the German city of Neubrandenburg in northern Germany. After uncoupling four cars, the train continued on its way. I remained in Neubrandenburg. On the outskirts of the city, a camp had been prepared for us, which was already largely occupied. As it turned out, we were its last addition. We all underwent preliminary medical treatment, and some of us even had our clothes changed. I, for example, was given a worn suit. I noticed that the storeroom was filled with similar items. Most likely, these were the clothes of prisoners who had been killed in Nazi concentration camps.

The camp was surrounded by a single row of barbed wire. Guards stood only at the gates. There were ten barracks in the camp: four for men, four for women, one for storage and a kitchen, and another for medical facilities and a bathhouse. We worked at a factory that manufactured containers for aircraft bombs.

Once, before taking us to work, the camp commander approached me and asked through an interpreter what my profession was. Without hesitation, I replied, “Carpenter.” After a while, I was transferred to one of the storerooms and ordered to work in the camp. The storeroom contained many different boards, a workbench, and carpentry tools. My first task was to build a doghouse for the camp commander’s dog. Without thinking twice, I built a doghouse that was an exact replica of a chapel located about 300 meters from our camp, only, of course, “dog-sized.” The dog was pretty indifferent to my creation. The camp inmates quietly laughed at my creation and wondered who I was trying to impress: the dog or the camp commander himself. I just wanted the dog to live a little better than its owner. However, its “beautiful” life did not last long. When a high-ranking German official came to visit our boss one day, I was ordered to immediately destroy my architectural creation and make a normal place for the dog to live.

Being the camp carpenter gave me some advantages. Armed with a toolbox, I went everywhere. It was easy to get to know people. In the kitchen, I could always get an extra portion of gruel, and from the warehouse I could take a dozen potatoes to bake in the boiler room and distribute them to those who were particularly in need of support.

A head boy was appointed to maintain internal order in the camp. The perpetually sullen and unsociable Antonov initially aroused particular animosity among the camp inmates. From a certain point onwards, he never parted with his stick, which he was not averse to using on anyone’s back or head when the opportunity arose.

When he met me near the barracks, he said:

– You must do everything only as I instruct you.

– I understood the camp commander differently,” I replied and turned to leave. Antonov raised his voice:

– Are you aware that I am the head of the camp?”

I turned around, walked up close to him, and said quietly but firmly, “I advise you not to waste your energy. Focus on the people; the farm will manage without you.”

Antonov was taken aback. He understood me exactly as I wanted him to, that I had special powers from the camp commander. This conversation had consequences. Whenever he saw me anywhere in the camp, he would bow to me. If he entered a barracks, he would shout about some trifle, but when he saw me, he would immediately fall silent and leave. Others began to notice this and even asked what it meant. I invariably replied that he was probably afraid of my mustache. At this point, Mikhailov interrupted my story and asked me to tell him more about those I had called “volunteers.”

I continued:

– There was a doctor named Kovalev. He was a young man, about thirty years old. People in the camp said that he was capable of any kind of treachery. Both Antonov and Kovalev boasted that they had come to Germany voluntarily. But Kovalev had some obvious advantages: he spoke a little German and reported on camp matters to the camp commander without an interpreter. Then I realized that it was Kovalev who was responsible for the camp commander’s extremely hostile attitude toward Antonov. I also realized that I shouldn’t joke around with Kovalev. Once, when I was repairing a door in the medical unit, Kovalev came up to me and started talking. At first he was cunning, but then he began to open up more and more. No matter how the war ended, he reasoned, he had nothing to do in Russia. The Bolshevik spirit would never die out among the Russians, but in the West he would be able to find true freedom. He just had to win the trust of the Germans. Kovalev loved to philosophize and often spent long hours talking with the patients. But it took the camp inmates a while to realize that Kovalev would open only his body, not his soul. The camp owed this discovery to two young men who, after being discharged from the infirmary, went straight to a concentration camp.

I knew another “volunteer.” His surname was Pankratov, and he was about twenty years older than me (I was 36 at the time). He also called himself a “volunteer,” a former officer of the White Army, and spoke “a little” German. This did not endear him to the camp inmates. But it struck me that he avoided contact with the Germans and refused the position of camp elder that was offered to him. Through an interpreter, he convinced the camp commander that he was not suitable for the position due to his age and health. In addition, I noticed that, despite his poor understanding of German, every evening when he returned from the factory, he would take out a German newspaper and read it in a secluded place. How, I wondered, could he read German newspapers without knowing the language? I began to court him and then asked him directly to answer questions that had long interested me.

– What do you want from me? – he asked.

– Translate for me what the Germans are writing about the Eastern Front.

From that time on, not a day went by without us sneaking off somewhere in the boiler room to read the newspapers he brought from the factory. Listening to my commentary on German reports from the Eastern Front, he cheered up and then began to comment himself. Some time passed, and based on newspaper reports, I compiled a brief summary of the situation on the Eastern Front. Pankratov and I discussed at length the idea of writing and distributing such summaries in the camp. We decided that once a week I would write a draft, Pankratov would edit it so that it was written in broken Russian but still understandable, I would copy it in five copies in my clumsy left-handed handwriting, and we would distribute it at the factory, where there were many German and French workers in addition to Russians. In this way, these reports came to the camp from the factory and were passed from hand to hand.

Investigator Mikhailov stopped me:

– What was the name of that German newspaper?

– Most often, it was the fascist newspaper “Folkischer Beobachter.”

– So what truth could you possibly extract from this newspaper?” asked my boss Mikhailov.

– At first, we didn’t expect to find anything resembling the truth in this newspaper. However, when we later compared our reports with the English ones that occasionally came into our hands, we were convinced that we were not far from the truth. Indeed, when the Germans write that they are leaving one city after another in order to straighten the front line, it is not difficult to guess that they are simply retreating. When they write that they are successfully destroying “bandit” detachments in the Belarusian forests with the forces of several divisions, it means that the partisan movement in Belarus has become nationwide. I remember during the battles on the Kursk Bulge, after the Germans “abandoned” Orel and Belgorod, and the previous days had reported that the “Soviets” were losing 2,500 to 3,000 tanks every day, an article suddenly appeared that could be distributed among our people without any alterations or comments. The article was called “Where did the Soviets get so many tanks?” It turns out that during the first five-year plans, large industrial complexes were built in the Urals and Siberia to produce tractors, combine harvesters, and other machines. And even before the plants were launched, the plant managers had secret plans in case of war to start producing certain weapons without any signal. Tanks were sent to the front, along with powerful mobile repair shops to fix them. That’s why tanks that had been knocked out by the “valiant German troops” were soon firing at the Germans again. Not a bad article, huh?

– Have you ever read newspapers published in Germany in Russian? Mikhailov asked.

– The translator I mentioned earlier, the son of a Russian émigré, worked at a factory and only came to the camp when called. Over the course of a year, he brought such newspapers to the camp three times, but we found nothing there worthy of our attention.

– Go on, said Mikhailov’s boss.

In the camp, people spontaneously gravitated toward each other. Groups formed where they exchanged news and opinions and made plans. Often, our “five” found out about these plans. And often we dismissed them because they were ill-conceived and dangerous. However, there was one disaster we were unable to prevent. A woman from our camp poured sand into a factory machine. She was quickly exposed. The next day, she and four of her friends were taken away from the camp. We were officially informed that they were being sent to a concentration camp to be exterminated.

One day, one of our group of five told me that he had met an old German man at the factory. He had been a prisoner of war in Russia during World War I and knew a little Russian. His son was a communist and, if still alive, was somewhere in a camp or prison. The old man offered to bring us two pistols and a dozen rounds of ammunition. I advised him to take the weapons from the old man, but not to take them to the camp right away, as everyone was thoroughly searched when leaving the factory. I knew a place in the camp where we could hide the weapons for the time being. A week later, our pistols were already there. A woman helped us get them out of the factory. Women weren’t searched as thoroughly. With the help of specially sewn bags, she easily smuggled them past the guard under her skirt.

A little later, two young men who had been at the front decided to organize an escape. After lengthy preparations and discussions with them, I informed them that they would receive weapons. We gathered bread (which we did not eat ourselves) for the men for the journey, and I stole as many potatoes as I could. The men had to avoid revealing themselves until they reached Poland. Late one evening, I made a small hole in the barbed wire and the guys left. After that, I never heard anything more about them. Sorry, I don’t go into much detail about camp life.

– Then you will write to us about those you remember well, regardless of how you feel about them,” said Chief Mikhailov. “Now answer the question: when did you leave the camp?

– In 1943, at the moment when the tide was turning in favor of the Soviet troops in the battles on the Kursk Bulge.

– How did the camp react to the news of the German defeat at Stalingrad?

– Almost everyone was happy, but only to themselves. Of course, the fascist government even declared mourning for the 300,000 soldiers who had died. I even remember one incident. There were two German carpenters who worked constantly in the camp, building various additional rooms. I often had to communicate with them. But this was very difficult, as neither I nor they spoke the language. But then one day, during the days of mourning, the interpreter I mentioned earlier suddenly invited me to an unfinished warehouse. Two German carpenters were already waiting for me there. The interpreter informed me that they would like to know my opinion on the events in Stalingrad. I was taken aback by this unexpected question. In turn, I asked them through the interpreter how they felt about Hitler’s party. The interpreter smiled and translated my question. The workers exchanged glances and nodded encouragingly. One of them spoke at length to the interpreter. The interpreter then turned to me and said:

– We understand your apprehension, but please believe us when we say that we would like to know the truth. If you are not going to be honest, there is no point in continuing this conversation.

Well, I guess whatever will be, will be. Almost an hour, maybe more, had passed since we started talking. I don’t think I’ve ever thought so hard about what to say as I did then. While the interpreter was translating, I thought hard about the next sentence. One of the workers stood guard at the half-open door the whole time. I don’t know how long the conversation would have lasted if the camp commander hadn’t appeared. The interpreter squeezed my hand above my elbow and left. A minute later, I followed him.

– Okay. Now tell me how you left the camp, – Mikhailov asked.

– Once, the camp elder Antonov summoned me to his office. For some reason, I had a bad feeling about it. Usually, he would come to find me himself. I went to see him. Without any preamble, Antonov announced: “The Germans want to send some people back home to Ukraine. One or two people from each camp. A collection camp is being organized in Berlin, from where the deportation will take place. I am offering you this trip.”

I was interrupted by investigator Mikhailov:

– Tell me straight, were you offered to attend courses?

-You’re wrong to talk to me like that, – I replied. – I’m just telling you how it was. I’ll get to the description of this camp myself.

-Well, well, we’ll see,- muttered Mikhailov.

– So, I started to press Antonov to tell me what else he knew besides what he had already told me. But he assured me that he knew nothing more. ‘And if I refuse?’ I asked. Antonov replied that there would be plenty of others willing to go. Almost everyone in the camp wanted to return home. I asked him to give me until tomorrow to think about it. In the evening, I gathered a few people. Old Pankratov, who didn’t talk to anyone else in the camp, also came. We thought long and hard about what to do. What did this mean? Maybe some kind of sabotage school? Unlikely. The Nazis weren’t stupid enough to entrust the selection of future spies to the head of a camp of Russian slaves. So, probably, they really want to send some of the Ukrainians back to their homeland. But why? After much discussion, we came to one conclusion. They need to show them that the new recruits are safe in Germany. But the Nazis won’t just let them go that easily. So they would brainwash them in Berlin. From this point of view, it would probably be training courses. And they wouldn’t leave us alone in Ukraine either; they would use us for propaganda work. So what to do? Go or not? The question arose as to why I had been chosen. But there was no disagreement on this point. Everyone knew about our strained relationship with Antonov and concluded that he had simply decided to get rid of me. There were many opinions about my departure. One said that I should definitely go, as it would be easier to escape from the Germans, but that it would be difficult to join the partisans and I might even be killed as a spy. Another agreed that we had to go, but that it was impossible to predict from here what to do and where to go in Ukraine. We would have to act according to the circumstances. Pankratov remarked that they might not send us to Ukraine while things were still going on in Berlin, because Ukraine would be liberated and there would be nowhere to send us.

Berlin – assembly camp for returnees from Ukraine

I turned to investigator Mikhailov and said:

– So, I was well aware that these would be courses, and yet I expressed my willingness to attend them. Are you satisfied with this interpretation?

– Quite, – Mikhailov smiled.

– Therefore, it was not my doing that these were not courses at all.

– Not courses? Then what were they?

– I think you can understand that it was not easy for me to make such a decision, but it was even harder to sit out the war behind enemy lines. And when the opportunity arose to return to my homeland, even if it was occupied, it was difficult to stay put. On the other hand, if I stay alive, I will have to hide the fact that I was in Germany from my compatriots, and that’s not easy. If they find out, you can never prove that you’re not a traitor. Right?

– Okay, continue, Mikhailov grumbled.

-The same factory translator took me to Berlin. I’ve forgotten what street it was.

-Could you point it out on a map? Mikhailov’s boss asked.

-Obviously, yes.

A map of Berlin was spread out in front of me. It had probably been prepared in advance. That meant they knew more about me than I did myself. After studying the map for a couple of minutes, I pointed out the location of these so-called “courses.”

– That’s right… Now tell me more about it, – asked Chief Mikhailov.

– Through the gate, you enter a spacious courtyard surrounded on two sides by the blank walls of neighboring three-story houses. In the center of the courtyard was a small building. Behind it was a gate and an exit to a parallel street. In the building, we were given several rooms with wooden two-story bunks, like in a camp. The other rooms were used as an office, a dining room, and a storeroom. There was another mysterious room with chairs and a table. It was logical to assume that lectures on anti-Soviet topics were held here. However, nothing of the sort was observed. In general, there was a lot of tension here when it came to reading. Once every ten days or so, a tabloid newspaper in Russian would appear, and there were also two small books that, in principle, no one read. One of them was about Zionists. I didn’t even bother to leaf through it, as it had been published during the fascist era. But I read the second book from cover to cover. It was religious in nature, published in 1923. At that time, I read a lot of similar literature, including, of course, the Bible.

I arrived at the camp in the afternoon. For dinner, we were given some kind of thin soup without bread. Bread was only given at breakfast—200 grams for the whole day. In the morning, we had coffee, and at lunchtime, soup, which was slightly better than in the camp. There were just over fifty people in the camp. We weren’t given any classes, and most of the time we didn’t even know what to do. Anti-Soviet propaganda consisted of the following. Every day, the camp commander, an old man of about sixty named von Schreiber, came to us for lunch. He would sit in a prominent place, eat his soup with gusto, and when he had finished, he would address the camp inmates with a “fiery” speech. Characteristically, he spoke in Russian. In general, it was a tirade of insults directed at those in front of him: they weren’t sitting properly, they weren’t looking properly, and so on. In the end, he lashed out at all Russians as a group. “In Russia, you walk around in bast shoes even in the city. I saw it myself. And in your collective farms, everyone sleeps under one blanket. And if you want milk, you go to the cowshed and milk the cow yourself.” Someone told me that this von Schreiber had lived in Russia as an agent before the revolution. Now he was a senile old man who had lost his mind. His ten-minute speeches were so similar that if you recorded one of them on a gramophone record, you could play it every day as dessert without von Schreiber himself. Despite the fact that there were very different people in the camp, including those with anti-Soviet sentiments, this afternoon rambling annoyed everyone without exception.

– What else, apart from von Schreiber’s ‘speeches’, can you remember? asked Mikhailov.

– During the two and a half months I spent in Berlin, we were visited by only two people who replaced von Schreiber in his afternoon speeches. On those two days, von Schreiber was forced to remain silent. No discussion was allowed after the fifteen-minute speeches of these guests. The first guest introduced himself as an employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He said that Germany had been forced to attack the Soviet Union, otherwise the Soviets would have captured Germany. The other had deserted from the Soviet army and spoke about the situation at the front. He explained that the Germans were forced to retreat because they could not breathe due to the decomposing corpses of Soviet soldiers. It was not easy to endure these humiliating lies.

I have already mentioned that there was plenty of free time in the camp. People gravitated toward each other, but the fear of encountering a provocateur or informer was stronger. Even those who were anti-Soviet were afraid, as rumors were increasingly reaching us that the German army was suffering crushing defeats. Everything related to food was a favorite topic of conversation. People with nothing to do involuntarily listened to their appetites and the state of their stomachs. The camp was poorly guarded. There was one man standing at the gate, appointed from among the camp inmates. Many of these “guards” paid no attention to the daredevils who ventured to wander around Berlin. It was impossible to get anything to eat, as everything in the shops was distributed on ration cards. We had neither ration cards nor money. It was believed that Eastern workers were paid wages, but this was only on paper. The amount deducted from us for security (by whom?), food, and maintenance in the camp was many times greater than the marks we were credited with. In other words, we were also left in debt. I learned that before my arrival, about thirty people from this camp had been sent to Ukraine. No work was done with them, except for the “titanic” efforts of that moron von Schreiber. Now there was no talk of sending us to Ukraine, as the Germans were constantly retreating. The question arose: where to put us? Send us all back to the camps where we had been before, or place us in a camp for Eastern workers.

I got to know more and more people in this motley camp. From what I observed, everyone was completely demoralized. Some were depressed because they would not be able to get to Ukraine, while others feared for their lives, as they were afraid of the arrival of Soviet troops in Germany. They lied to themselves that the German army was invincible. I felt an overwhelming desire to support some and condemn others. I too often forgot that there could be, and most likely were, Gestapo agents among us. I soon found this out for myself when, in September 1943, the secret police came for me and I was arrested.

Berlin-Alexandraplatz – Gestapo prison

– We know everything else about you from the Gestapo archives we seized, as well as from the testimony of those who were with you in prison and in the concentration camp. Just answer a few questions. Why did you not heed Pankratov’s wise advice and refuse to travel to Berlin? After all, Pankratov warned you that the time was not far off when the Germans would be unable to deport you to Ukraine.

– First, I already mentioned that it was difficult for me to sit in Neubrandenburg while the war was raging in the east. Second, I did not expect Hitler’s military machine to collapse so quickly and believed that I would still end up in Ukraine. I would like to note that at that time there was no second front yet, and Soviet troops had to fight alone against fascist Germany, which had mobilized the industrial potential of the whole of Europe. I also waited anxiously to see how Turkey and Japan would behave, against whom, no doubt, a considerable part of our forces had been diverted. I did not expect the complete defeat of the fascists before the end of 1945.

– Do you know who betrayed you to the Gestapo?

– I don’t know. Maybe Oparin. He introduced himself as an engineer, the son of Academician Oparin. He often listened to my conversations, and from some of his comments it was clear that he had a negative attitude toward everything Soviet.

– Yes, there was a man named Oparin, but he was not an engineer or the son of an academician. He was a simple salesman who had been in prison for fraud. However, he did not betray you. It was someone named Irshinsky. Do you remember him? He had been recruited by the Gestapo before the war.

Yes, of course I remembered Irshinsky. He never spoke about his worldview, but always tried to engage me in frank conversation.

– Where is he now? In prison? – I asked.

– No. He serves us and is currently where he has been ordered to be. Now tell me, to put it mildly, what mistakes have you made during this time?

– It’s easy to analyze your past now. To find mistakes, as it turned out. But at the time, I thought I was doing everything right. I came to the railway hut where the Germans were, instead of lying in the cornfield until dark. But because of my concussion, I wasn’t thinking straight, and all I could think about was getting to water. Well, if I had approached that hut at night, they would have simply shot me, because I couldn’t run. To avoid falling into the hands of the Germans, I could have settled down with some old people in Ukraine. It would have been possible to look for such an opportunity. However, I cannot imagine how I could have hidden for a long time at that time. And in general, although I do not believe in any predestination, I felt doomed from the very beginning. After my arrest, I believed that my fate was sealed, as I knew that there were only two ways out of the fascist torture chambers: either execution in prison or a slow death in a concentration camp.

– Why didn’t you make any notes in these camps so that you could pass them on to us if you survived?

– It was impossible to keep such notes after going through prison and the camps. I gave some of my notes to a woman from this collection camp, but there was nothing significant in them.

-What was this woman’s surname?

-I don’t remember.

Chief Mikhailov leafed through the folder. Then he said:

-Her surname was Kravchenko. She also wrote something about you. There was nothing significant in your notes, but some of it was useful to us.

-Where is Kravchenko now? – I asked.

– In her homeland, in the Odessa region. If you are interested in this question, I will provide you with the exact address later. Now, tell me, with whom did you maintain contact outside of these ill-fated courses?

– No one.

– And who did you leave the camp so often to visit?

– Ah, I see… You know that too. Kravchenko must have written to you.

– Not only Kravchenko.